Key to first Jewish Cemetery in Quebec City

Organization: Exposition Shalom Quebec

Coordinates: www.shalomquebec.ca

Address: 1035 rue du Mont Saint Denis Quebec, QC G1S 1A7

Region: Quebec City Region

Contact: Simon Jacobs, simjac1035(a)gmail.com

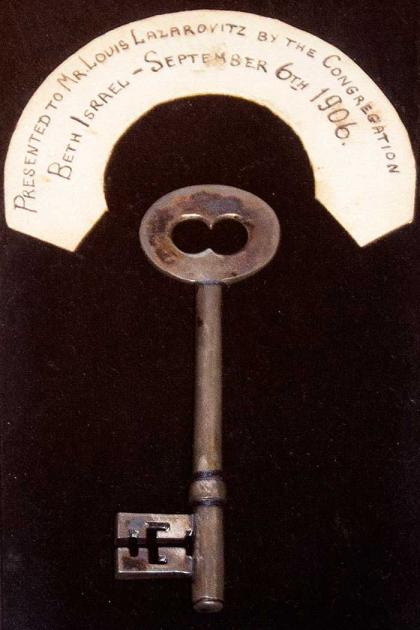

Description: Key to the first Jewish Cemetery in Quebec City, mounted in a wood-framed box with a glass cover. Inscription: “Presented to Mr. Louis Lazarovitz by the Congregation Beth Israel – September 6th 1906.”

Year made: circa 1850s

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Steel

Colours: Silver-grey

Provenance: Unknown

Size: Key: 10 x 3 cm. Frame: 30.5 x 17 cm

Photos:(1,2) Rachel Garber. Courtesy Marge Lazarovitz; (3,4) Courtesy Exposition Shalom Quebec.

Jewish Cemetery Key

Simon Jacobs

There has been a Jewish presence in Quebec since they first arrived with the British in 1759. Before that, Jews were not allowed into New France, as it was open only to Catholics. They settled and formed communities in Quebec City, Trois Rivieres, Montreal, and later in Sherbrooke. Today the largest communities remain in and around Montreal.

The community was already established in Montreal with the opening of the Spanish and Portuguese (Shearith Israel) synagogue in 1768. But it was not until the beginning of the 1850s that a formal community (Beth Israel) was established in Quebec City, even though there had been a Jewish presence since the 1760s. The community mainly consisted of English and German merchants and businessmen.

Around the same time the community became established, land was privately bought to serve as the community’s burial ground. This cemetery had to be created outside of the city’s limits due to new ordinances that had been passed to avoid the propagation of cholera, of which there had been previous outbreaks. Louis Lazarovitz, one of the first Eastern European Jews to arrive in Quebec City in the 1880s and who had a shop on St. Joseph Street, was handed the key to the cemetery in 1906 by the English owner of the land who had bequeathed it to the synagogue. A 1960s sound recording of the late Sidney Lazarovitz, Louis’ son, reveals more about the cemetery's history:

“Basically in Quebec there were two Jewish communities. There was a community here years ago which we have little knowledge of, which consisted we believe mostly of merchants in the import-export business or the lumber business. They came mostly from England. And I believe around the 1890s or 1900s they disappeared. Our cemetery was their cemetery. One day a gentleman presented himself at my late father’s business, he was the last member of this community and this was their burial ground and he turned it over to the new community, where Jews that came mostly from Rumania, Russia and that was the beginning of this community.”

The community that Sydney Lazarovitz speaks of began to form in the late 1800s, when the first Jews from Eastern Europe started arriving in Quebec City in search of the promise of a better life for their families. In some cases, the men-folk would arrive and settle, followed by their wives and children who would come a few years later. The new immigrants did not really integrate with the more established English/German community, preferring to create their own communities with their own customs. This clear delineation between the two communities was probably due to the more relaxed and integrated form of English and German Judaism that did not correspond with the stricter interpretations of Jewish law and traditions practised by the Jews arriving from Eastern Europe.

This community settled in the poorer lower town section of Quebec City, close to the main shopping area of St-Roch and also close to the port of Quebec and the railway stations. At one point there were three synagogues operating in the city: Beth Israel, located on Grant Street, Ohev Sholom on Ste-Marguerite Street catering to the Polish and Lithuanian Jews, and a small synagogue located on Henderson Street for the Russian Jews, probably located in the back of a store.

The cemetery was taken over by Beth Israel in 1906 and the community later amalgamated with Ohev Sholom in 1927.

The main synagogue in the first half of the 20th century was located in the lower town at 21 Ste-Marguerite Street. The synagogue was built in the traditional manner typical of Eastern Europe: two stories high with two balconies for the women facing each other and running the length of the building, looking down on the ground floor where the men would pray. The bima (table from which the Torah scrolls are read) and Ark (containing the Torah scrolls) were located at the eastern wall with benches facing on either side. Above the central aisle of the synagogue was a barrelled ceiling and the balconies were supported by evenly spaced pillars. Windows were placed on the northern and southern walls.

It was only in 1944 that the Community was able to build a new synagogue in the wealthier upper town after many public objections to their buying the land. Even then, the basement was firebombed the night before its official opening, but no significant damage occurred since there were community members on hand to put out the fire.

The construction of the new synagogue was spearheaded by Maurice Pollack, a prominent Quebec City businessman. He arrived with five cents to his name in 1902, speaking Yiddish but no English or French, like most of the other Jewish immigrants. Arriving in Halifax, he moved to Quebec City and started work as a peddler. Established members of the community helped set him up with some goods and then assigned him a route. It is important to remember that the vast majority of French Canadians lived in the rural areas of Quebec, where public transport was not available and there were no shops. Once he had saved up enough money he bought a store on St-Joseph Street, which he kept on growing, transforming it into one of the largest department stores in Quebec City. In addition, he got involved in the manufacturing business and real estate. He not only helped the Jewish community but also contributed to the Greek Orthodox community, Laval University, where the student building is named after him, the Quebec High School and many other causes.

When you look at the Jewish cemetery today, you will notice that the graves are lined up, set closely together in rows. This probably reflects the European cemeteries, where Jews did the same, due to restriction of the space they were allowed to use. You will notice also the absence of statues. This derives from the second of the Ten Commandments “You shall not make for yourself a carved image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

Instead you will find a wealth of symbols are used: a broken tree trunk or pillar denotes a person died early in life, two hands, palms pointed out in the form of the priestly blessing, shows that the person buried there was a member of the Cohenim or priestly class; a Star of David; an image of a Torah scroll; an image of the ten commandments on two tablets or a lamp, symbolizing the lamp that hung in the temple. The gravestones are not necessarily elaborate and are often written in Hebrew, giving the name of the deceased,  his or her father’s name and the date the person passed away according to the Jewish calendar. You may also note that some of the graves have pebbles placed on the top, as it is customary, when visiting a grave, to leave a small stone on the gravestone as a sign of respect.

his or her father’s name and the date the person passed away according to the Jewish calendar. You may also note that some of the graves have pebbles placed on the top, as it is customary, when visiting a grave, to leave a small stone on the gravestone as a sign of respect.

In spite of the cultural divides that occurred between the different Jewish traditions in the community while they were alive, it is in the cemetery today that you will find them lying side by side. In 1992 the cemetery received official designation as a National Historic Site from the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Traditionally, after a person dies, a shomer (watchman) is assigned to sit with the body until the body is prepared for burial. The preparation of the body is carried out by members of the chevra kaddisha (holy society), where it is respectfully and ritually washed. The gender of those preparing the body will be the same as the deceased. Jewish belief holds that we are all equal in death, so the body is dressed in simple white linen. The coffin (generally used in Quebec) is also supposed to be as simple as possible and be made entirely out of wood, with no metal used in its fabrication or as ornamentation. Cremation is not carried out in Jewish tradition as it is believed the body should naturally return to the earth as quickly as possible. As there is no embalming, the burial ceremony is carried out as quickly as possible, usually within twenty-four hours.

As long as there has been a cemetery in Quebec City, there have been members of the community ready to help with the Chevra Kaddisha. Today the community has diminished in size and changed once again from being English-speaking with East European roots to more linguistically mixed, with many members coming from North Africa or France. The synagogue that was built in the upper town was sold in the 1980s to become a theatre and a smaller building was bought near the Plains of Abraham.

The key stands to remind us about the changing nature of the community and the story of all the people that helped contribute to it. It not only unlocks the cemetery but it unlocks the past.

Sources

Guy Wagner Richard, Le Cimetière Juif de Québec : Beth Israël Ohev Sholom, 2000.

Rachel Smiley, “Historic Sketch of the Quebec Jewish Community and Synagogue”, Dedication of the Beth Israel-Ohev Sholom Synagogue and Community Centre (Quebec, 1944), http://eglisesdequebec.org/ToutesLesEglises/swNotreDameDeJacquesCartier/...

To Learn More

Denis Vaugeois and Käthe Roth, The First Jews in North America: The Extraordinary Story of the Hart Family of Quebec, 2012.

Ira Robinson, “No Litvaks Need Apply”: Judaism in Quebec City, Concordia University, www.cjs.concordia.ca/...papers...jewish.../Workingpapers3IraRobinson.pdf

Irving M. Abella, A Coat of Many Colours: Two Centuries of Jewish Life in Canada, 1990.

Tulchinsky, Gerald, Canada’s Jews. A People’s Journey (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2008).

Author

Simon Jacobs is the Executive Director of Exposition Shalom Quebec.

Comments

Empress of Ireland Jewish Victims

Is there any information about the 1914 Jewish drowning victims of the Empress of Ireland that were buried in Quebec City? The Mount Hermon cemetery CPR monument, lists 9 unidentified adults and 1 child that were buried in the Jewish cemetery. Further research has shown that one body, Josefta Zuk (Zouk?) a child, was buried on June 2, 1914 in Quebec City. Her father survived the tragedy, but lost his wife and 2 children. Many thanks for any information you can send to me. irvosterer [at] rogers.com

Jewish cemetery

There was a history of the cemetery written by a French Canadian academic that was on the internet, but is no longer. Guy Wagner Richard??? When I saw it (about 15 years ago) I noticed a photo of my great grandfather who was on the board of the chevra kadisha. His name was Nathan Fickler. Do you have any information about that book? Or other information? Nathan came to Canada in 1893 and settled in Lac St Jean, but moved to 3-Rivieres and then Quebec City. (before moving later to Montreal).

Sari Shernofsky

Add new comment