DRUM

Organization: Missisquoi Museum

Coordinates: www.missisquoimuseum.ca

Address: 2 rue River, Stanbridge East, QC J0J 2H0

Region: Montérégie

Contact: Heather Darch, info(a)missisquoimuseum.ca

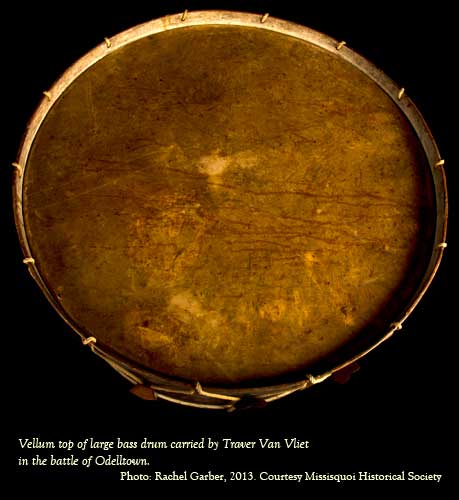

Description: Large bass drum carried by Traver Van Vliet in the Battle of Odelltown, the last conflict of the Rebellion of 1838.

Year made: circa 1837

Made by: Unknown, hand painted by H. Miller Dieu et mon Droit/Honi soit mal y pense (God and my right/ Let he who thinks ill there be shamed)

Materials/Medium: Wood, vellum, leather

Colours: Natural, red, black

Provenance: Lacolle, Quebec

Size: 81.5 cm diameter x 48 cm high

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Missisquoi Historical Society

FLAG

Organization: Hemmingford Historical Archives

Coordinates: hfordarchives(at)gmail.com

Address: CP 1006, Hemmingford, QC J0L 1H0

Region: Montérégie

Contact: Mary Anne Ducharme hfordarchives(a)gmail.com

Description: Rebellion Regimental Flag of the Hemmingford Loyal Volunteers. A large royal blue silk flag presented to the Hemmingford Loyal Volunteers to commemorate their victory over the Patriote forces at the Battle of Lacolle, 1838.

Year made: 1839

Made by: Handmade by Mrs. Gilchrist

Materials/Medium: Silk

Colours: Blue, red, white, gold

Provenance: Montreal, Quebec

Size: 2 m2

Photos: Courtesy Canadian Museum of Civilization

The Rebellion of 1837-1838 Flag and Drum

Heather Darch and Mary Anne Ducharme

The rise of the Patriote movement in the 1830s was a decisive turning point in Quebec’s history. In Lower Canada the seeds of insurrection were hastened by a period of economic disenfranchisement of the French-speaking majority and working class English-speaking minority, the British government’s refusal to alter the structure of colonial government and the complex issue of language and culture between the English and French. For Louis Joseph Papineau, the spokesman of the Parti Canadien, Lower Canada was a distinct and important territory to be preserved as a French-speaking and Roman Catholic home for its inhabitants.

Criticism increased of the English-speaking merchants who controlled the Legislative Assembly and of the English-speaking elite who were disproportionately represented in both the timber trade and in financial institutions. When Britain rejected the Patriotes’ demand for control of provincial expenditures by the Assembly, Patriote leaders initiated a programme of public rallies. For a few weeks in the autumn of 1837, Patriotes controlled parts of the countryside near Montreal. British troops were called to restore order. The situation deteriorated into an armed rebellion, most notably at St. Charles and St. Eustache and many Patriotes were arrested, while others fled to the Richelieu Valley or across the American border.

In northern Vermont and New York, Patriotes refugees received support from American sympathizers eager to assist their cause against British imperialism. The Patriote cause was also well supported in Eastern Townships' communities such as Stanbridge East and Dunham, which saw American republicanism as a positive alternative to British imperialism and land control. Throughout the winter of 1837 and into 1838, support of these political refugees grew and, most certainly, weapons and money reinforced this moral support. Within the English-speaking community, deep divisions were keenly felt as entire villages were known to support either the Patriote cause or the government's position. Even neighbours and family members split in disagreement.

In February 1838, Robert Nelson (1794-1873) officially proclaimed the founding of the “Republic of Lower Canada” which would embody the ideals of the Patriote movement, including religious freedom, separation of church and state and access to public education. Calling themselves “La Société des Frères-Chasseurs” or Hunter's Lodges, these new radical Patriotes, who had disassociated themselves from Papineau, saw armed insurrection as the only logical step to gaining their freedoms.

In the context of the Rebellion, the Township of Hemmingford was in the “bull’s eye.” It was an English-speaking settlement with an international border as its southern boundary. It was settled mainly by Americans who had declared their loyalty to George III at the end of the American Revolution. It was the home to immigrants from Great Britain. And it was surrounded by French-speaking seigneuries teeming with unrest. Among United Empire Loyalists in Hemmingford, allegiance to the British Crown had been tested in the fires of the American Revolution, and again in the War of 1812. Progressive-minded people might voice sympathy with the obvious suffering of habitants on the seigniorial lands, but expression of this view in Hemmingford, where patriotism was synonymous with the Crown, was cause for deep suspicion.

Under such suspicion was John Scriver, the son of Loyalists from Rhinebeck, New York. Scriver was a man of principle and was outspoken when it came to the need for change. He was also a pragmatic man, busy as a major employer in the area in lumbering, potash making, and road building. He would advocate vigorously for French-speaking citizens within the existing system, but he drew the line on radicalism and rebellion. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, and in 1838 he was on the Huntingdon County Militia pay list. Such militias were critical to the support of the government of this era when there were only five regiments in all of Canada.

Throughout 1838, people living in this border region lived with increasing anxiety as rumours of impending attacks by the Patriote exiles and their American sympathizers continued to build. In early November, those loyal to the Patriote cause from the surrounding parishes, gathered at Napierville under the command of Robert Nelson and C.H.O. Côté. On November 7, 1838, volunteer and British troops met the Frères-Chasseurs at Lacolle, Quebec. After a pitched battle lasting just 25 minutes, the rebels retreated. Nelson immediately directed his men to Odelltown where on November 9, 1838, forces met yet again.

Headed by Lewis Odell, Charles McAllister and John Scriver, loyalists engaged Patriotes at the Odelltown Methodist Church. The rebel forces under the command of Robert Nelson, Médard Hébert and Charles Hindelang initiated the “hot firing” around 11 o'clock in the morning. According to Robert Sellar’s History of Huntingdon County, Colonel Scriver charged his Hemmingford volunteer militiamen to shoot him if they doubted his loyalty. He rode up and down the marching column on his buff-coloured horse shouting encouragement and held his sword high while grape shot peppered the air around him. Scriver ordered the charge that finally routed the Patriotes from the field. After two hours of combat, and severely outnumbered and outgunned, the Patriotes began to break up and flee across the border. The bell in the Methodist church “tolled the death-knell” of the Patriote movement.

John Scriver was awarded a sword, a stand of colours and a 462-acre land grant in recognition of his military services. What became of the sword is unknown, but ironically the flag, much more fragile, survived the intervening years. It was hand sewn and presented by the women of Hemmingford on May 9, 1839, to commemorate the Battles of Lacolle and Odelltown. The regimental flag, which included the young Queen Victoria's monogram, and its companion Queen's Colours (Union Jack), were donated to the Canadian War Museum by the Hemmingford Archives. The regimental flag was restored by the Canadian Museum of Civilization textiles conservation laboratory.

The bass drum, which is housed at the Missisquoi Museum, was carried in the Battle of Odelltown by Traver Van Vliet (1800-1890), an ensign with the “Odelltown Loyal Volunteers.” On November 9, 1838, Ensign Van Vliet sounded the drum to march the volunteers into battle and, ultimately, to victory. In 1849, the Rebellion Losses Bill granted Van Vliet £30 for damaged property and a stolen horse. The drum was conserved by the Centre de conservation du Quebec.

Both the drum and flag are the only artefacts known to exist from the Rebellion era which represented the loyalist forces of 1838.

Sources

J.I. Little, Loyalties in Conflict: A Canadian Borderland in War and Rebellion 1812-1840, 2008.

“The Moore’s Corner Battle,” Missisquoi Historical Society Fourth Annual Report 1908-1909.

Beverly Boissery, A Deep Sense of Wrong; The Treason, Trials and Transportation to New South Wales of Lower Canadian Rebels after the 1838 Rebellion, 1995.

Elinor Kyte Senior, The Rebellions in Lower Canada 1837-1838, 1985.

Denyse Beaugrande-Champagne, “Les mouvements Patriote et loyal dans les comtés de Missisquoi, Shefford et Stanstead, 1834-1837,” Université du Québec à Montréal, Master's thesis.

Allen Greer, The Patriotes and the People: The Rebellion of 1837 in Rural Lower Canada, 1993.

Robert Sellar, The History of the County of Huntingdon Quebec and of the seigniories of Chateaugay and Beauharnois from their settlement to the year 1838, 1888.

To Learn More

Jacques Monet, The Last Cannon Shot: A Study of French Canadian Nationalism, 1967.

Desmond Morton, Rebellions in Canada, 1979.

Francois Ouellet, Social and Economic History of Quebec, 1981.

Rebellion History www.collectionscanada.gc.ca

Authors

Heather Darch is the curator of the Missisquoi Museum. Mary Anne Ducharme is the archivist of the Hemmingford Historical Archives.