Theban Mummy, Male

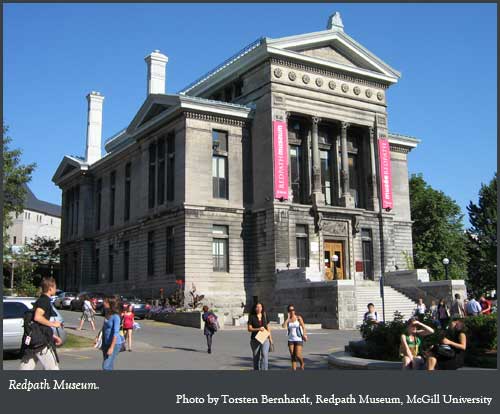

Organization: Redpath Museum, McGill University

Coordinates: www.mcgill.ca/redpath

Address: 859 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, QC H3A 0C4

Region: Montreal

Contact: Barbara Lawson, Curator of world cultures barbara.lawson(a)mcgill.ca

Description: Egyptian mummy in its open sarcophagus.

Year made: 332-30 BCE, Ptolemaic Period

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Mummified human remains and wrapping

Colours: Dark brown with buff coloured wrapping

Provenance: Thebes, Egypt

Size: 1.56 m long

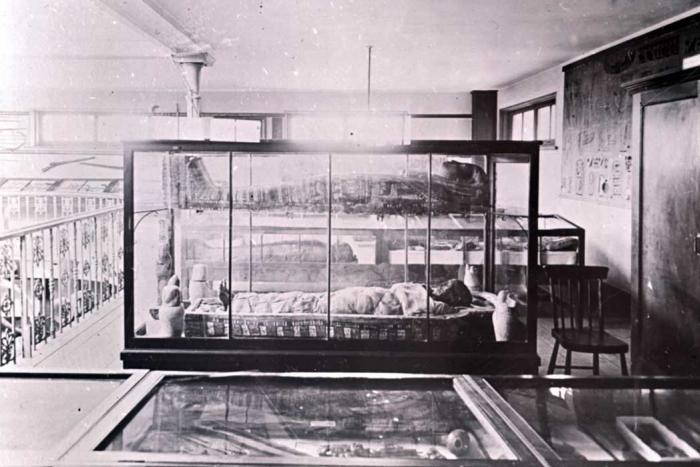

Photos: (1-2) Torsten Bernhardt, Redpath Museum, McGill University. (3) Rachel Garber. (4) Photograph by glass lantern slide, Mummy Cases, Natural History Society Museum, Montreal, QC, about 1900. © McCord Museum. MP-0000.25.236

The Natural History Society’s Mummy

Rod MacLeod

Nineteenth-century Montrealers, Anglophones especially, were often amateur naturalists and collectors of all sorts of specimens. Protestant clergymen were particularly drawn to scientific investigation, a legacy of the Romantic Movement’s view of nature as a moral and spiritual force. This fascination would soon translate into a professional dedication to educating the general public in scientific matters, spawning an assortment of museums.

In May 1827, no less than three Presbyterian ministers (Henry Esson, James Somerville and Alexander Mathieson) joined forces with four doctors from the Montreal Medical Institution (Andrew Fernando Holmes, William Caldwell, William Robertson and John Stephenson), along with an assortment of lawyers (including John Samuel McCord) and merchants, to found the Natural History Society of Montreal. This, the oldest scientific organization in Canada (Quebec’s Literary and Historical Society is older, but not specifically devoted to science), established a mandate to promote the study of natural history, above all by means of a museum that would house its members’ collections. A few years before, Thomas Delvecchio had opened a “Museo Italiano” above his St. Paul Street tavern, which featured a sensational assortment of stuffed animals, wax figures, and freaks of nature. Leaders of the Natural History Society were determined to create a much more dignified exhibition, and located their museum in a more prestigious building on the much grander St James Street.

Donations from the Society’s dozens of members soon transformed its museum into a significant collection of rocks and minerals, plants, shells, insects, reptiles, mammals and birds. The enthusiasm of both donors and amateur custodians was such that the collection expanded beyond what is normally considered natural history to include coins, historical memorabilia, and even curiosities such as might not have been out of place in the Museo Italiano.

The Society’s museum also had over 90 works of art, including the cast of the Discobolus that Samuel Butler discovered decades later in storage, apparently kept out of sight so its nakedness would not offend the public. In his infamous poem “Psalm to Montreal,” Butler used the puritanical dismissal of the statue as a metaphor for the city’s supposed cultural backwardness. In reality, what the museum lacked was a degree of professional knowledge and curatorship. It received both in 1841, when the National Geological Survey established its headquarters in the Society’s museum. Sixteen years later, renowned geologist and McGill University principal John William Dawson joined the Society’s board and brought much-needed improvements to the management of the collection.

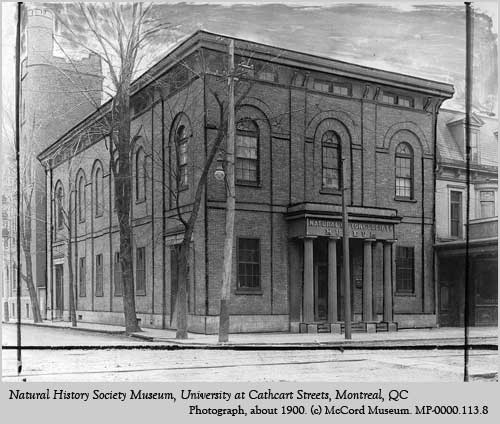

Another prominent member was James Ferrier, a wealthy hardware merchant, municipal politician, and governor of McGill University. His influence, and Dawson’s, secured new and larger premises for the Society on university-owned land on Cathcart Street. The year the new museum opened – 1859 - Ferrier took a sabbatical from his many concerns and travelled to Europe and the Middle East. He returned with a number of antiquities he had purchased in Egypt, including a more than 2000-year-old mummy from Thebes. In what may well have been the most exotic gift in the museum’s history, Ferrier donated these souvenirs to the Natural History Society, where they were given a place of honour.

The designation of Ottawa as the nation’s capital eventually obliged the Geological Survey to move away from Montreal, taking its share of the collection with it; eventually the Survey would become the National Museum of Canada. With a much reduced collection, the Montreal museum tried to attract visitors by displaying artwork, but these attempts were undermined by the 1879 opening of the Art Association of Montreal’s new gallery around the corner on Phillips Square.

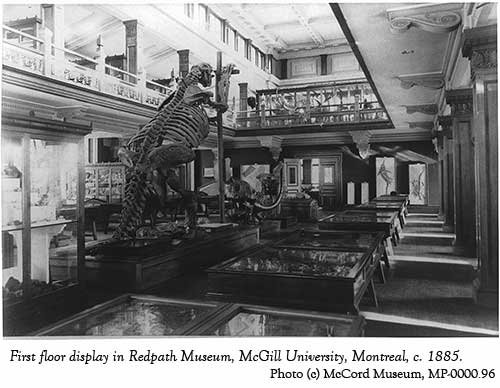

The Natural History Society’s fortunes declined even further when a frustrated Dawson decided to establish a separate museum under the wing of McGill University that would feature his own collection and serve as a teaching tool for students. He convinced the wealthy Redpath family to fund the construction of an elegant museum, designed by Montreal architect Alexander Cowper Hutchison, on the McGill campus.

This, reputedly the first purpose-built museum in Canada, featured a monumental stairway, Egyptian columns, and huge windows that allowed a steady supply of natural light. When its doors opened in 1882, the Redpath Museum’s vast central hall contained a somewhat idiosyncratic exhibit showing flora and fauna arranged in such a way as to reflect Dawson’s own views on the evolution of life on earth, which were at some distance from Darwin’s. Over the years, the exhibit has been vastly changed to reflect the latest research on evolution and other scientific matters, but the shape of the grand hall has remained essentially intact, along with the unique Victorian lecture theatre on the ground floor.

Without Dawson, the Natural History Society’s museum was once again a largely amateur affair. It continued to function until 1906, when the Cathcart Street building was sold and the collection packed away for shipment to a new location. Unfortunately, relocating proved too expensive, and the artefacts remained in storage until 1925 when the Society folded.

The collection was dispersed. Artworks found their way into the Art Association Gallery (later the Museum of Fine Art), where, with more space, the Discobolus was at last displayed properly. Historical items were absorbed into the McCord Museum of Canadian History, which had opened in an old house on Sherbrooke Street in 1921. The natural history holdings, along with most ethnographical items, went to McGill University – including Ferrier’s Egyptian collections, which are now displayed in the Redpath Museum’s third-floor gallery. They are a curious symbol of that urge to investigate and collect that prompted Montreal’s Anglophone elite to create an array of museums that continue to delight and educate.

Sources

Susan Bronson, “The Design of the Peter Redpath Museum at McGill University: The Genesis, Expression, and Evolution of an Idea About Natural History,” M.Sc.A Thesis, Université de Montreal, 1992.

Stanley Brice Frost, “Science Education in the Nineteenth Century: the Natural History Society of Montreal, 1827-1925,” McGill Journal of Education, Vol.XVII, No.1 (Winter 1982).

Hervé Gagnon, “The Natural History Society of Montreal’s Museum and the Socio-Economic Significance of Museums in 19th Century Canada,” Scientia Canadensis, vol.18, no.2 (47), 1994.

Barbara Lawson, “Exhibiting agendas: anthropology at the Redpath Museum (1882-1899),” Anthropologica (Journal of the Canadian Anthropology Society), v. XLI, n. 1, 1999.

Barbara Lawson, “Egyptian Mummies At the Redpath Museum: Unravelling the History of McGill University’s Collection,” Fontanus, (forthcoming 2013).

Neale McDevitt, “That’s a wrap: mummies undergo non-cutting cutting-edge examinations at The Neuro,” McGill Reporter, May 5, 2011.

To Learn More

Visit the Redpath Museum, McGill University www.mcgill.ca/redpath

Mummification www.ancientegypt.co.uk/mummies/home.html

The Egyptian Afterlife legacy.mos.org/quest/afterlife.php

Are You My Mummy? Mummies and Imaging and Teaching, oh my http://areyoumymummy.com/tag/redpath-museum/

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.