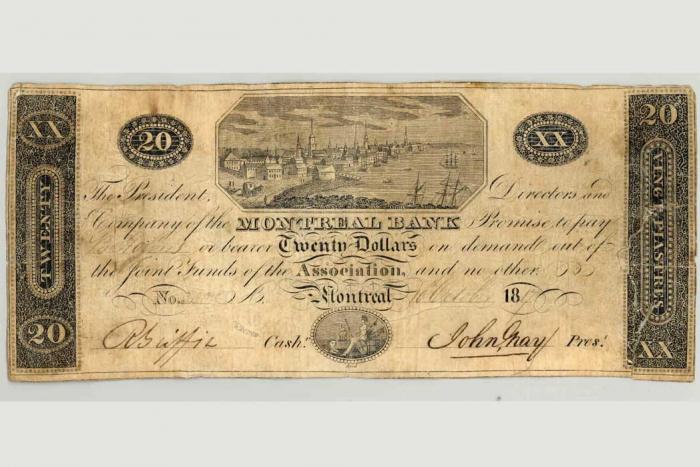

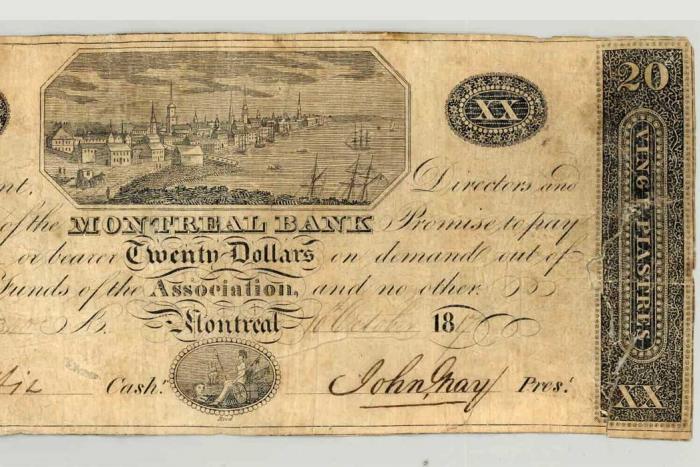

Banknote, 1817

Organization: Bank of Montreal Museum

Coordinates: www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/mus_attr/eng/pop_musees.htm

Address:128 St-Jacques Street, Montreal, QC H2Y 1L6

Region: Montreal

Contact: Yolaine Toussaint, yolaine.toussaint(a)bmo.com

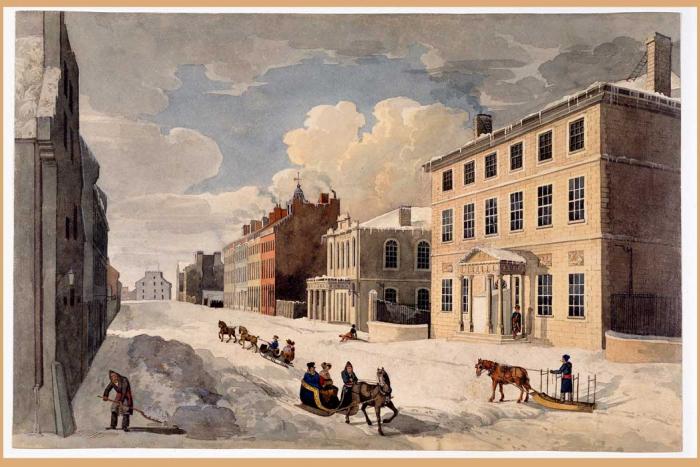

Description: (1-2) A $20 bill from the Bank of Montreal’s first year of operation as the “Montreal Bank.” (3) Forgery plate of a Bank of Montreal banknote. (4) Saint-James Street, Montreal, 1830. Painting by Robert Auchmuty Sproule.

Year made: 1817

Made by: Montreal Bank

Materials/Medium: Paper, ink

Colours: Brown, grey

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 18 cm x 10 cm

Photos: (1-2) Courtesy Service des archives, BMO Groupe financier; (3) Courtesy Missisquoi Museum; (4) © McCord Museum M300

Financing Quebec

Rod MacLeod

It is a mantra of Quebec history that Anglos were masters of finance. Individually, they might not all have even been very good at math, but collectively theirs was a financial world, rather than an artistic or spiritual one.

This view is supported by some circumstantial evidence (the Protestant “work ethic,” Scottish frugality) as well as by some more tangible historical explanations (access to imperial markets, a practical education system), but at the end of the day essentialist arguments are inevitably defeated by the details. Francophones were always involved in business; moreover, as is the case in most other Quebec institutions over the last few decades, high finance is now dominated by the linguistic majority.

That said, for historical reasons, the rise of a banking system in Quebec was largely spearheaded by English speakers.

Finance is less about making money than it is about creating the means by which money can be made. Banks are not creatures of capitalism, but rather the reverse. Leaving aside classical academic debates over the transition from “traditional” economies to “modern” ones (represented by a shift from basic barter to stock markets and venture capital), the issue usually boils down to getting one’s hands on cash.

A system based on barter, mutual obligation, or small-scale credit works well if there are few commodities in circulation. “Traditional” societies can function this way for generations (and did, everywhere) but introduce a sudden demand for a local resource (fur, timber), or a desire for faster transport, and neither barter nor credit is sufficient for the necessary transactions. Building steamboats required specialized technology and a dedicated workforce that had to be paid.

Some successful merchants were able to marshal this kind of money, usually with the profits from selling fur or timber, but most could not. Any plans to produce commodities (foodstuffs, clothing, furniture, tools) more efficiently, and to move them to potential new markets more quickly, were all but unattainable – not without cash. And furthermore, cash had to mean something. One of the biggest problems with finance in “traditional” societies was that there were no standard currencies. When people bought and sold, they fumbled with louis, guineas, crowns, dollars, livres, and an array of questionable bits of paper money, some of which resembled playing cards. Lack of standards essentially meant lack of business.

The early 19th century was an age of ambition in Lower Canada. The conclusion of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 promised an end to economic stagnation caused by trade blockades, but the supply of money was still faulty. Inspired by institutions already emerging in Britain and the United States, Montreal merchants had been planning to establish a Canadian bank since the 1790s. The driving force behind this move was John Richardson, Scottish fur trader turned fiercely pro-British politician, who assembled fellow merchants George Moffatt, Robert Armour, Horatio Gates, and (the token Francophone) Augustin Cuvillier to form the Montreal Bank.

These men pooled their resources and invited public subscriptions, offering investment opportunities with limited liability – a critical feature of capitalist enterprise whereby individuals were not personally liable (above the amount of their initial investment) should bankruptcy or some other disaster occur. The Montreal Bank immediately won public confidence and was established as a private company, capitalized at £250,000. Richardson chose not to sit as a director; the bank’s first president was veteran fur trader John Gray. As cashier (essentially bank manager), the directors hired Robert Griffin, the man whose wife Mary had subdivided the Montreal neighbourhood that would be known as Griffintown.

On November 3, 1817, the bank opened its doors to customers, who could now deposit any savings they might have, or even borrow money for some potentially profitable enterprise. Cash came in the form of banknotes, issued with Gray and Griffin’s signatures, which represented for the bearer a specific amount, guaranteed by the bank, that could be exchanged for goods. By officially standardizing the currency, the Montreal Bank became the precursor to today’s Bank of Canada, which since its creation in the 1930s regulates national monetary policy and issues banknotes.

Significantly, the Montreal Bank’s notes were in dollars, a stable and easy-to-calculate currency, even though Canadians would continue to negotiate in pounds, shillings and pence for another 40 years. The Montreal Bank soon had its competitors: the Bank of Canada (not to be confused with today’s crown corporation), the Bank of British North America, the City Bank, and the Banque du Peuple – not to forget private banks such as Molson’s, or smaller banks set up away from the financial metropolis to encourage local business, such as the Quebec Bank and the Eastern Townships Bank in Sherbrooke. All these institutions issued their own banknotes, but it was the well-capitalized Montreal Bank (soon renamed Bank of Montreal to distinguish it from other banks operating in the city) that set the standard currency for the entire colony for many years.

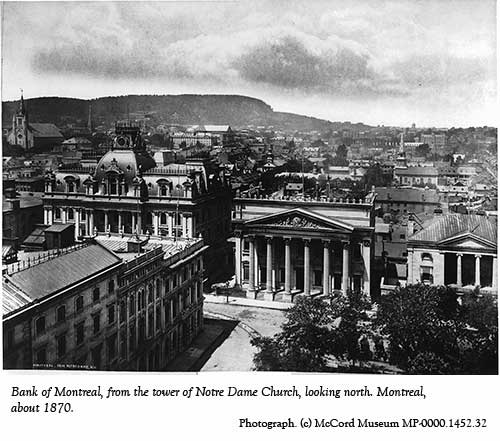

In 1819, the Bank of Montreal settled into its first purpose-built headquarters, on St. James Street, which would soon become the heart of Canadian finance. This elegant Georgian building was decorated at Richardson’s insistence with four terra cotta plaques representing agriculture, arts and crafts, navigation, and commerce – all values of an enterprising spirit that men of British origin promoted, along with those of other backgrounds who had bought into this vision.

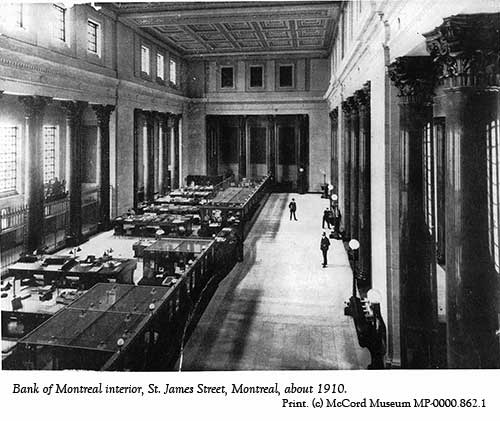

By the 1840s, an even more confident spirit prompted the replacement of the bank building by a much larger structure designed by local architect John Wells as a pseudo-Parthenon with six massive Corinthian columns facing Place d’Armes. (The terra cotta plaques were saved from demolition and eventually found their way into the interior corridor of the current Bank of Montreal building.) The new bank’s main concourse, modelled after the monumental Baroque churches of Italy and the world’s grand railway terminuses, was designed to impress. It was from this headquarters that countless civic projects were funded, from the widening of the Lachine Canal to the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway – the latter made easier by having men sit as directors of both bank and railway company.

By the late 19th century, the Bank of Montreal had serious rivals in Toronto-based institutions such as the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and the Bank of Toronto, both of which had branches on St. James Street, and the Royal Bank of Canada, whose head office moved to Montreal from Halifax in 1907. Unlike the latter, which famously took its headquarters from St. James Street to Place Ville Marie in the 1960s, the Bank of Montreal remained in its original location. Like the Royal Bank, however, the Bank of Montreal’s operational head office moved to Toronto in 1977 – perhaps the most telling example of the shift of power from Canada’s oldest financial centre to its oldest rival.

Sources

Michael Bliss, Northern Enterprise: Five Centuries of Canadian Business, Toronto, 1987.

Merrill Denison, Canada’s First Bank: A History of the Bank of Montreal, Toronto, 1967.

Guy Pinard, Montreal: son histoire, son architecture, Montreal, 1987.

To Learn More

John Richardson: Dictionary of Canadian Biography On Line www.biographi.ca

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.