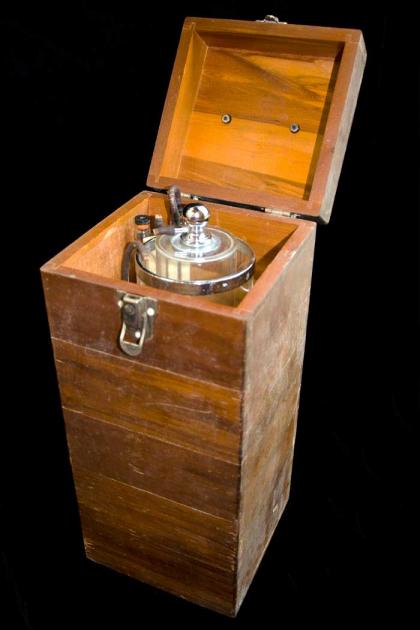

Bethune Pneumothorax Machine

Organization: Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University

Coordinates: www.mcgill.ca/library/library-using/branches/osler-library

Address: 3655 Promenade Sir William Osler, Montreal, QC H3G 1Y6

Region: Montreal

Contact: Christopher Lyon, christopher.lyons(a)mcgill.ca

Description: A small device for forcing air through tubes and cylinders into a tubercular lung designed by Norman Bethune.

Year made: c.1930

Made by: Geo. P. Pilling & Son Company

Materials/Medium: Glass, metal, plastic

Colours: Clear, buff

Provenance: Philadelphia, USA

Size: 36 cm tall x 15 cm in diameter (base) and 10 cm diameter (tubes). Wooden box measures 17.5 cm x 17.5 cm x 41 cm.

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University

Norman Bethune and a Healthy Society

Rod MacLeod

The most famous Canadian in history was launched on the road to fame by collapsing lungs in Montreal.

In the 1920s, the Royal Victoria Hospital had clear fault lines, reflecting those in society at large: Specialists looked down on generalists, women interns were few (Jessie Boyd Scriver was the first, in 1922), private rooms and public wards were poles apart in terms of comfort, and senior doctors treated students, orderlies, and even patients (if they were poor or had little command of English) with contempt. Many specialists had, of course, earned their medical stars on the battlefields of World War I and were used to strict discipline, but others felt such attitudes interfered with teaching and added to the miseries of those who could barely afford to consult a doctor. Criticism of outdated approaches and techniques was growing, but nothing prepared the medical establishment at the “Vic” for the arrival of Norman Bethune in 1928.

Bethune had grown up in Ontario and studied there, as well as in London and Edinburgh. Having seen active war service in France, he too understood the need for discipline when it came to saving lives, but he was also conscious of the futility of healing men only to see them further injured in battle. He would come to see the same futility in treating industrial workers for ailments that would swiftly recur thanks to wretched working and living conditions. Bethune was also an innovator, an attitude that would lead to much frustration in Montreal but to countless lives saved in Spain and China.

While being treated for tuberculosis in an American sanatorium, Bethune read extensively about the artificial pneumothorax (AP) process. Developed largely on the battlefield, AP involved inserting a hollow needle between the ribs and through the pleural lining; air was then pumped in, pressing the lung flat and allowing it to rest so the patient could recover faster. Bethune insisted that AP be used on him. When he recovered, he accepted a position in the new Pulmonary Clinic at the Vic in Montreal, where his attentive and sympathetic bedside manner impressed students and reassured patients. Against established practice, he staunchly advocated AP over surgery, which he thought dangerous and expensive. Existing pneumothorax machines were huge and heavy, however, and could not be brought to the patient. Bethune designed his own light and compact version of the machine, which he sent to be manufactured at George Pilling & Son of Philadelphia. Reputedly, his contract with these makers of surgical equipment stipulated that a mechanic by the name of Masters be given the sole rights to market Bethune’s device in Canada. Bethune was not interested in making money off his invention.

Bethune clashed with the medical establishment over the use of such techniques, but even more over his determination to apply his skills to help the city’s poor. Bethune opened a free clinic for unemployed workers and their families, and assembled a small team of doctors willing to give their time gratis. He became convinced that charging for medical services was wrong. “Take the profit out of Medicine,” he famously declared to a gathering of health administrators whose objective was usually to keep fees as high as possible. By the mid-1930s, Bethune was drawn to Canada’s Communist party, which he believed was the only force capable of overcoming capitalism and its commodification of all things, including health.

The Depression had brought the inequalities of industrial society to the surface and revealed the inadequacies of existing political forces to alleviate misery. Left-wing movements emerged, advocating greater government control over health and welfare, even over the economy. In Montreal, the League for Social Reconstruction (LSR) gathered around lawyer F.R. Scott and economists Eugene Forsey and Leonard Marsh, all of whom would have a profound influence on Canada’s postwar economy and political culture. The LSR helped found a new party, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, which preached an alternative to the established parties, but won no seats in Quebec during the 1935 federal election and only one in the 1944 provincial election. Bethune was sympathetic to the LSR and the CCF, but criticized their pacifism, especially in the face of the rapidly-growing right-wing movements in Quebec, including the home-grown fascists who had trashed his apartment and painted it with swastikas.

The issue that marshaled political feeling in Quebec was the Spanish Civil War. In July 1936, a partly successful military coup divided Spain into two camps: The rebels were backed by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, while the Popular Front government (composed of Socialists, Communists, and Liberals) was aided by the Soviet Union. Western states claimed neutrality; Canada even made it illegal for citizens to participate. Nevertheless, volunteers joined the International Brigades to defend the Spanish Republic, which to many on the Left represented a moral stand against fascism.

Bethune was prompt to volunteer, along with several Montreal activists, including architect Hazen Sise, with whom Bethune set up the Canadian Medical Unit in Madrid. The Spanish capital lay near the territory controlled by the right-wing Nationalists and received huge numbers of wounded. Sensing that many were dying of blood loss before they could reach hospitals in the city, the ever-innovative Bethune organized a mobile blood transfusion service, involving a network of ambulances which toured the countryside, often at great peril. After six months of this gruelling work, Bethune returned to Montreal to campaign for funds. This proved a thankless task: politicians in Quebec were inclined to support the Nationalists as a bulwark against the “Reds,” whose violence against the Spanish clergy horrified Catholics. Bethune was disillusioned, but soon heard of another compelling foreign struggle, and in early 1938 he departed for China to help Mao’s forces resist the invading Japanese army. He died the following year from an infection caught while operating on the battlefield.

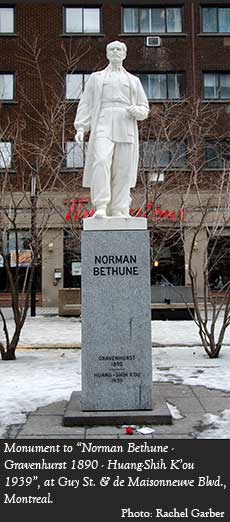

For years, Norman Bethune was remembered in Canada only as one of the more colourful of the interwar intellectuals, but in China he was revered as a hero. After Mao’s victory, the exploits of “Comrade Bethune” became required reading throughout the People’s Republic, making him a more familiar figure world-wide than any other Canadian. In the 1970s, Canada began to warm to Bethune just as it opened up to China after Prime Minister Trudeau’s 1973 visit. Sise, who had led the Bethune Memorial Committee since its creation in 1939, campaigned for public recognition of Bethune. It came, after much negotiation, in the form of a statue erected in 1978 in what was to be known as Place Norman Bethune, near Concordia University. This was ironic, given Bethune’s affiliations with McGill institutions. McGill, however, was host to the 1979 symposium marking 40 years since Bethune’s death, featuring presentations on the man’s medical achievements as well as his poetry and painting. Several books and films appeared, including the 1990 feature, Bethune: the Making of a Hero.

Canadians have been wary to embrace Bethune as a hero, in no small part because of his association with communism. What they cannot deny is his courage, and his almost reckless commitment to treating the sick and wounded in the most horrific of circumstances.

Sources

Ted Allan and Sydney Gordon, The Scalpel, the Sword: the Story of Doctor Norman Bethune, Toronto, 1952.

Adrienne Clarkson, Extraordinary Canadians: Norman Bethune, Toronto, 2009.

Loren Lerner, “The Unmasking of Dr. Norman Bethune,” Journal of Canadian Art History, vol.XXXI:1, 2010.

Wendell MacLeod, Libbie Park, and Stanley Ryerson, Bethune: the Montreal Years, Toronto, 1978.

Mark Zuehlke, The Gallant Cause: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, Mississauga, 1996.

To Learn More

Bethune Memorial House National Historic Site of Canada, http://www.pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/on/bethune

Library and Archives Canada, www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/physicians/030002-2100-e.html

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.