Book: The Principal Navigations

Organization: Stewart Museum

Coordinates: http://www.stewart-museum.org

Address: 20 chemin du Tour-de-l’Isle, Montreal, QC H3C 0K7

Region: Montreal

Contact: Sylvie Dauphin, info(a)stewart-museum.org

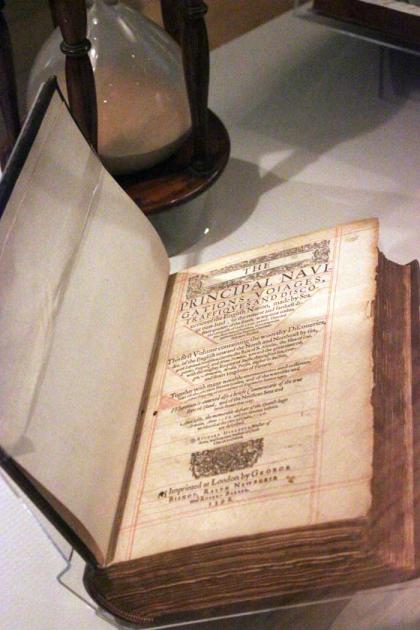

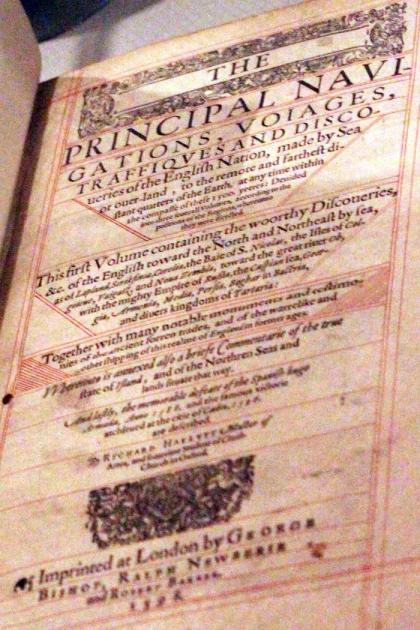

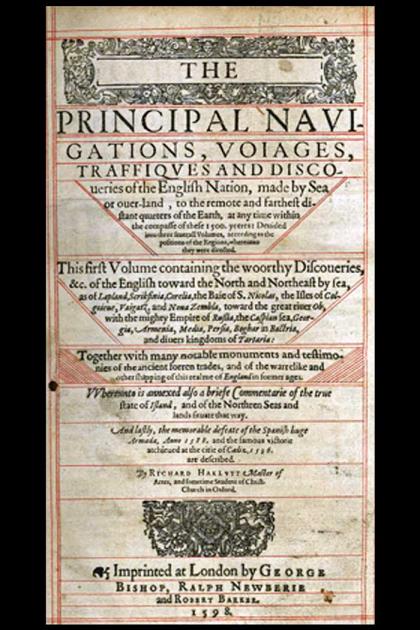

Description: First volume of The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation by Richard Hakluyt, a late 16th century three-volume book, nearly 1000 pages long. Depiction of the writer Richard Hakluyt in a stained glass window in the Bristol Cathedral (West Window of the South Transept).

Year made: 1598

Made by: Printed by George Bishop, Ralph Newberie, and Robert Barker

Materials/Medium: paper, binding

Colours: greenish brown

Provenance: England

Size: approximately 28 x 20 x 10 cm

Photos: (1-3) Courtesy Musée Stewart Museum. (4) By Charles Eamer Kempe. (Bristol Cathedral.) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

An Explorer’s Guide to the World

Rod MacLeod

The British Empire began at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1572. Admittedly, before that time there had been plenty of explorers hailing from England who journeyed great distances by land and sea seeking new commodities to import. Some journeys were supported by the crown, including the one in the 1490s that had taken the Italian John Cabot to the eastern shores of what is now Canada.

In the middle decades of the 16th century, however, the English crown was embroiled in dynastic and religious issues and was less inclined to endorse overseas adventurers. During this period, the French crown was more active, backing voyages such as Jacques Cartier’s. He brought back tantalizing information about sources of potential wealth up the vast river valley he named Saint-Laurent.

By the 1560s, the French and English positions were reversed: France was in religious turmoil while England saw greater stability under Queen Elizabeth, who was even prepared to support expeditions. She endorsed John Hawkins’ efforts to involve England in the slave trade and expand its navy. A fleet to defend the island made good sense, especially in the expectation that Spain would attempt an invasion.

But it was only in the 1570s that an even more ambitious vision emerged, namely that England should use its sea power to expand its reach around the world and even establish colonies. The most vocal proponent of this vision was Richard Hakluyt, son of a London skinner.

Orphaned at an early age, Hakluyt was raised by a distant cousin who owned a collection of maps and cosmographies with which he instructed his young charge. He convinced Hakluyt that the Bible (notably the 107th Psalm) encouraged Christians to “go down to the sea in ships” and “do business in great waters.” Hakluyt was so impressed that, after completing his initial duties as a scholar at Christ Church, Oxford, by 1572 he set himself the task of reading every account of voyages and discoveries he could lay his hands on. He began giving public lectures on geography, making liberal use of maps and globes and other scientific instruments.

Overseas adventure was very much in the air at this time, especially once courtier Humphrey Gilbert had persuaded the Queen of the usefulness of finding a “North West” passage across the arctic ice connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific. Beginning in 1576, Martin Frobisher led several useful but ultimately unsuccessful voyages to the frozen north. Both Gilbert and his half-brother Walter Raleigh launched sailing expeditions, which amounted to little. Much more sensational were the campaigns of Francis Drake who, after cutting his teeth on his cousin John Hawkins’ South American adventures, was given his own commission. In 1577 he embarked on a voyage that would eventually take him right round the world.

Hakluyt, meanwhile, had gotten as far as France. Having published his first book, which chronicled the early voyages to the Americas, Hakluyt was appointed secretary to the English ambassador in Paris on the strength of his knowledge; the position involved a degree of spying. He was enraged to hear French scholars dismiss the English contribution to geographical discovery. He began compiling a collection of accounts of expeditions, based on his earlier studies at Oxford. By that time, Gilbert was trying to promote the establishment of overseas colonies. In 1583 he attempted to start one himself in Newfoundland, dying in the process.

Raleigh was keen to pursue this ideal, and commissioned Hakluyt to write a discourse on the need for colonies in America. Hakluyt presented this book to the Queen in 1584, hoping to obtain royal support for Raleigh’s proposed colony on Roanoke Island, which he would call Virginia. Elizabeth was more concerned about the Spanish threat, and Hakluyt returned to France and his compiling.

The climate following the victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588 restored much confidence in the possibilities for English adventure. The bible of this spirit of enterprise was Hakluyt’s long-awaited masterwork The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation. Appearing initially in 1589 but in a revised and expanded three-volume version in 1598-1600, the book contained hundreds of accounts of previous travels to all corners of the earth, chiefly those by English explorers. It also included a few token outsiders, such as Jacques Cartier. It also contained a passionate plea for investment in a Virginia colony. The Virgin Queen herself was dead by the time this enterprise took off, but in 1606 her successor James I granted a charter to the Virginia Company with a mandate to found two colonies along the American seaboard. Hakluyt’s knowledge was invaluable to these expeditions, even though he had acquired all his expertise from reading the works of others.

Apart from his geographical knowledge, Hakluyt inspired a century of English exploration and colonization with the conviction that it was all in the service of divine will. Just as the biblical psalm had spoken of God favouring those who did business in great waters, so did Hakluyt promote the mission of Protestant England to defeat the forces of Catholicism, be they in South America or along the St. Lawrence Valley. Principal Navigations set the stage for an imperial rivalry that would see British forces under William Phips attempt to take Quebec City in 1690 and another British army under James Wolfe do so successfully in 1759.

Sources

Winston S Churchill, The New World, 1956.

J.H. Elliott, Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America, 1492-1830, New Haven, 2006.

G.R. Elton, England Under the Tudors, London, 1991.

Richard Hakluyt, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, Edmund Goldsmid (editor), 1884.

Christopher Hill, The Century of Revolution, 1603-1714, 1961.

To Learn More

Ramsey Cook, The Voyages of Jacques Cartier, 1993.

Martin Frobisher www.canadahistory.com

Humphrey Gilbert - Dictionary of Canadian Biography www.biographi.ca

Francis Parkman, Count Frontenac and New France, 1877.

“Sir William Phips’ Attack on Quebec, 1690,” in Introduction to the study of military history for Canadian students, ed. C. P. Stacey 1960.

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.