Chrysotile Asbestos Organization: Musée minéralogique et minier de Thetford Mines Coordinates: www.museemineralogique.com Address: 711 Frontenac Blvd West (Route 112), Thetford Mines, QC G6G 7Y8 Region: Chaudière-Appalaches Contact: Geneviève Clavet Roy, 418-335-2123, service.client(a)museemineralogique.com Description: A piece of Chrysotile Asbestos extracted from Thetford Mines Year made: 1881 (mine opened) Made by: The forces of Nature Materials/Medium: asbestos minerals Colours: Grey, silver, black Provenance: Thetford Mines Size: approx. 30 cm x 25 cm x 25 cm Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Musée minéralogique et minier de Thetford Mines

Chrysotile Asbestos

Jessica van Horssen This is a piece of chrysotile asbestos taken from the deposit found at Thetford Mines. Asbestos is a fireproof mineral that resembles a woolly rock. It can be broken apart, woven, or packed into a variety of products to make them stronger and able to withstand heat up to 3000˚F. In the photographs, you can see a band of white asbestos fibres running horizontally through the middle of the rock. Historically, these fibres were included in military uniforms, firefighting equipment, paint, household insulation, oven mitts, aprons, and cement. Industry experts quickly termed Quebec’s asbestos “white gold” because of its colour and value, and by the mid-20th century, it was actually worth more than gold in international markets.  Massive amounts of asbestos were discovered in the northeastern portion of the Eastern Townships near Thetford in the 1870s with the construction of the Quebec Central Railway. The claim to this discovery was contested between an Anglophone named Robert Ward and a Francophone named Joseph Fecteau, which illustrates how the culture of the region was changing in the second half of the 19th century. The Eastern Townships were originally intended by the British crown to be an Anglophone settlement in Francophone Quebec, but the gradual industrialization of the region brought in a real mixture of English-speaking and French-speaking workers. The late 19th century was a time of massive resource development in the province, with mining being one of the principal industries expanding throughout Quebec. Historically, French Canadian workers were employed as miners in the mining industry, while Anglophones held positions in management, having had the opportunity to attend post-secondary education, to obtain professional degrees, and to have the start-up money required to open a mine. This was especially true in Quebec’s asbestos industry, as the mines were quickly purchased by international companies based in English Canada, the United States, and Great Britain: Speaking the language of company officials was a definite advantage for Anglophone workers, and they often acted as middlemen between company officials and French Canadian miners.

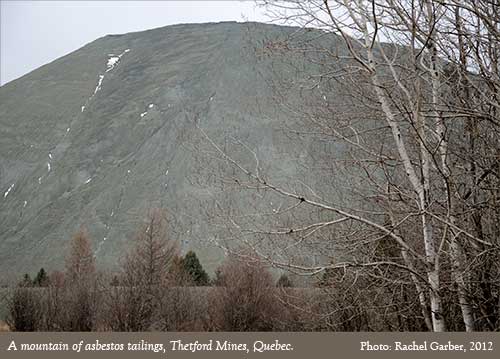

Massive amounts of asbestos were discovered in the northeastern portion of the Eastern Townships near Thetford in the 1870s with the construction of the Quebec Central Railway. The claim to this discovery was contested between an Anglophone named Robert Ward and a Francophone named Joseph Fecteau, which illustrates how the culture of the region was changing in the second half of the 19th century. The Eastern Townships were originally intended by the British crown to be an Anglophone settlement in Francophone Quebec, but the gradual industrialization of the region brought in a real mixture of English-speaking and French-speaking workers. The late 19th century was a time of massive resource development in the province, with mining being one of the principal industries expanding throughout Quebec. Historically, French Canadian workers were employed as miners in the mining industry, while Anglophones held positions in management, having had the opportunity to attend post-secondary education, to obtain professional degrees, and to have the start-up money required to open a mine. This was especially true in Quebec’s asbestos industry, as the mines were quickly purchased by international companies based in English Canada, the United States, and Great Britain: Speaking the language of company officials was a definite advantage for Anglophone workers, and they often acted as middlemen between company officials and French Canadian miners.  For many years the deposits at Thetford were considered the most extensive in the world and the area surrounding the growing community was known as Quebec’s “asbestos belt.” The discovery at Thetford coincided with a growing marketability for the mineral. American manufacturers had started to specialize in asbestos-based building products to meet the growing demands of industrializing America. The mines of the Eastern Townships quickly became places where different factions of the population—English, French, upper class, working class—would debate who controlled the land, and asbestos would often be central to this struggle. Quebec has a number of asbestos mines, with several located in Thetford. The largest in the world for much of the 20th century, the Jeffrey Mine, was located in the town of Asbestos. While underground mining was used in this industry, for the most part Quebec’s asbestos mines were opencast, with the Jeffrey Mine currently measuring 200 kilometres wide, and deeper than the height of two Eiffel Towers. At its peak, Quebec’s asbestos industry produced 95% of the global supply of the mineral, which amounted to an average of 30,000 tonnes of fibre and rock being taken from the mines each day by 1960. Anglophone engineers were essential experts in the creation of these massive opencast mines, ensuring landslides and groundwater did not ruin the deposits or harm the workers. The incredible degree of labour required to meet these extraction levels created a significant amount of dangerous mineral dust, which hovered in the air throughout Quebec’s asbestos communities in great clouds. Asbestos causes a variety of cancers, including that of the lung, skin and breast, and mesothelioma, a fast-acting cancer of the lining of the major organs. It also causes asbestosis, which is a hardening of the lungs that constricts their ability to expand and contract, leading to death by suffocation. The workers and residents of Quebec’s asbestos towns were significantly affected by the mineral dust that hovered in the air of their communities. Chrysotile asbestos has a complex legacy of being renowned as a magic mineral that saves people from the threat of fire, to a deadly hazard that causes fatal diseases; Quebec’s mines and workers have been central to this history. Sources P.B. Bourret, “Non-Metallic Mineral Deposits of the Province of Quebec,” The Canadian Mining Journal, October 1948, p. 162. “Geological Survey of Canada, Report for the Year 1888-1889,” (Montreal: Dawson Brothers, 1888-1889), p. 140K. “Geological Survey of Canada: Report for the Year 1919,” (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1919), p. 5A. Marc Vallières, Des Mines et des Hommes: Histoire de l’Industrie Minérale Québécois des Origines au Début des Années 1980 (Québec: Publications du Québec, 1989), p. 95. The Canadian Mining Journal, February 1960, p. 160. To Learn More History of Mining, www.mrn.gouv.qc.ca Asbestos Quebec: The Most Dangerous Town in Canada, www.cbc.ca The Canadian Asbestos Strike, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com Author Jessica van Horssen is an Assistant Professor in the History Department at York University. She has a forthcoming monograph on the history of the town of Asbestos, Quebec with the University of British Columbia Press entitled, Asbestos: Environmental Change, Contamination, and Collapse. She has also written a graphic novel about the town of Asbestos, which can be found here: http://megaprojects.uwo.ca/asbestos/

For many years the deposits at Thetford were considered the most extensive in the world and the area surrounding the growing community was known as Quebec’s “asbestos belt.” The discovery at Thetford coincided with a growing marketability for the mineral. American manufacturers had started to specialize in asbestos-based building products to meet the growing demands of industrializing America. The mines of the Eastern Townships quickly became places where different factions of the population—English, French, upper class, working class—would debate who controlled the land, and asbestos would often be central to this struggle. Quebec has a number of asbestos mines, with several located in Thetford. The largest in the world for much of the 20th century, the Jeffrey Mine, was located in the town of Asbestos. While underground mining was used in this industry, for the most part Quebec’s asbestos mines were opencast, with the Jeffrey Mine currently measuring 200 kilometres wide, and deeper than the height of two Eiffel Towers. At its peak, Quebec’s asbestos industry produced 95% of the global supply of the mineral, which amounted to an average of 30,000 tonnes of fibre and rock being taken from the mines each day by 1960. Anglophone engineers were essential experts in the creation of these massive opencast mines, ensuring landslides and groundwater did not ruin the deposits or harm the workers. The incredible degree of labour required to meet these extraction levels created a significant amount of dangerous mineral dust, which hovered in the air throughout Quebec’s asbestos communities in great clouds. Asbestos causes a variety of cancers, including that of the lung, skin and breast, and mesothelioma, a fast-acting cancer of the lining of the major organs. It also causes asbestosis, which is a hardening of the lungs that constricts their ability to expand and contract, leading to death by suffocation. The workers and residents of Quebec’s asbestos towns were significantly affected by the mineral dust that hovered in the air of their communities. Chrysotile asbestos has a complex legacy of being renowned as a magic mineral that saves people from the threat of fire, to a deadly hazard that causes fatal diseases; Quebec’s mines and workers have been central to this history. Sources P.B. Bourret, “Non-Metallic Mineral Deposits of the Province of Quebec,” The Canadian Mining Journal, October 1948, p. 162. “Geological Survey of Canada, Report for the Year 1888-1889,” (Montreal: Dawson Brothers, 1888-1889), p. 140K. “Geological Survey of Canada: Report for the Year 1919,” (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1919), p. 5A. Marc Vallières, Des Mines et des Hommes: Histoire de l’Industrie Minérale Québécois des Origines au Début des Années 1980 (Québec: Publications du Québec, 1989), p. 95. The Canadian Mining Journal, February 1960, p. 160. To Learn More History of Mining, www.mrn.gouv.qc.ca Asbestos Quebec: The Most Dangerous Town in Canada, www.cbc.ca The Canadian Asbestos Strike, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com Author Jessica van Horssen is an Assistant Professor in the History Department at York University. She has a forthcoming monograph on the history of the town of Asbestos, Quebec with the University of British Columbia Press entitled, Asbestos: Environmental Change, Contamination, and Collapse. She has also written a graphic novel about the town of Asbestos, which can be found here: http://megaprojects.uwo.ca/asbestos/