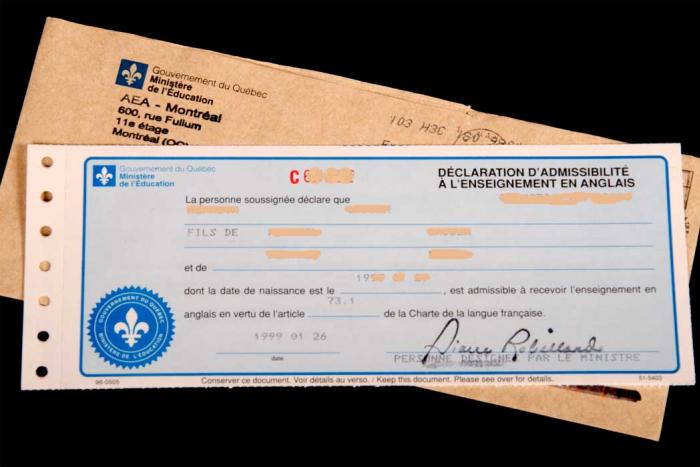

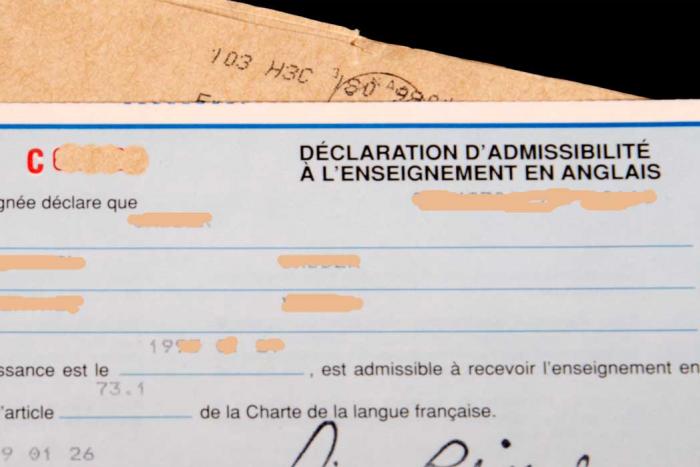

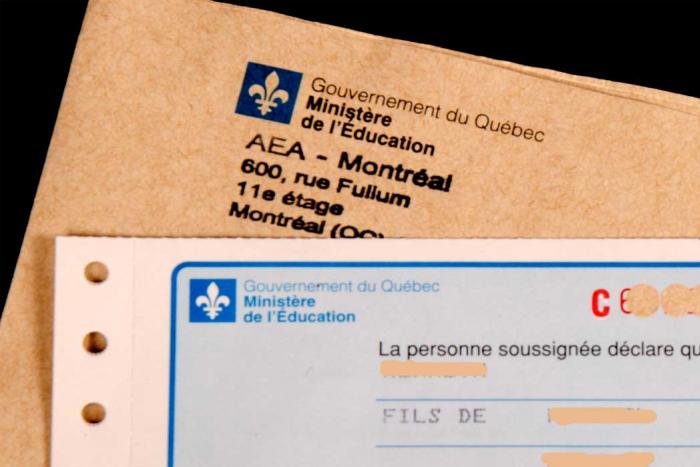

Eligibility Certificate

Organization: Missisquoi Museum

Coordinates: www.missisquoimuseum.ca

Address: 2 rue River, Stanbridge East, QC J0J 2H0

Region: Montérégie

Contact: Heather Darch, info(a)missisquoimuseum.ca

Description: Paper document issued by the Quebec government permitting English-speaking parents to send their children to school in English, providing that they too had received the majority of their education in English and in Canada.

Year made: 1999

Made by: Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère de l'Éducation

Materials/Medium: Paper

Colours: Blue, white

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 21 cm x 9 cm

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Missisquoi Museum

Certificates of Eligibility

Rod MacLeod

One of the most contentious political issues of recent years in Quebec has been access to education – not whether children from disadvantaged backgrounds or ethnic minorities may attend school, but under what circumstances children may go to school in English.

Since the 1970s, legislation has placed clear restrictions on who may attend English schools, provoking much resentment, even outrage, from those who feel this represents an infringement of basic rights. Those who fit the criteria are entitled to a “certificate of eligibility,” which in some circles becomes a highly desirable item. But not all who are eligible make use of the certificate, while many who do so today have agendas that would have surprised lawmakers of previous generations.

Contrary to what is often assumed, Quebec has only had an English school system (and a French one) since 1998. From the time of Confederation, Quebec schooling was organized along religious lines, with school boards designated as either “Protestant” or “Catholic” and with school taxes going to one or the other local board. The right to either Protestant or Catholic education was guaranteed by the British North America Act (modified in 1998 in order to create linguistic school boards); those from non-Catholic and non-Protestant backgrounds had no such guarantee, but were entitled to send their children to either system and, if taxpayers, to choose which confessional board they wished to support.

Unlike religion, the language of instruction enjoyed no constitutional guarantee. From the early days of public education, however, many Catholic school boards, especially in urban areas, established English-language sectors, which soon swelled with the arrival of Irish, then Italian, immigrants. For their part, some Protestant boards ran French-language schools for the province’s small but vocal Francophone Protestant population, above all in the Richelieu Valley and Montreal’s South Shore. In the early 1970s, the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal began opening French-language schools, largely in response to the desire for more religious and linguistic variety in education, as recommended by the Parent Report on the state of Quebec schooling. By and large, however, newcomers whose mother tongue was neither French nor English opted to send their children to school in English, believing it to be a key to integration into North American society.

The language legislation of the 1970s changed all this. For some time, many in Quebec – indeed, across Canada – had been expressing concern that the French language was fighting a losing battle against English, the language that most of the continent’s other linguistic minority communities had already adopted.

Some Quebec nationalists were willing to take aggressive measures to curb the influence of English. The first volley of this battle was fired in St. Leonard, a suburban municipality in the Montreal area with a large Italian population, much of whom attended school in English. In 1968, however, local Catholic school board elections returned a nationalist-minded majority who decided to close down its English sector, leading to widespread protests and a 7,000-member march on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. The Quebec government hastily drafted Bill 63, which obliged school boards to provide schooling in both languages and gave immigrants the right to choose which. In response, defenders of the St. Leonard board rioted in the streets, inadvertently winning public support for the legislation.

The October Crisis of 1970 further dampened public enthusiasm for violence, but the conviction that French needed protection remained strong. The Gendron Commission, established to study the province’s linguistic situation, identified the immigrant preference for English-language education as one of the threats to the survival of French.

The Liberal government’s 1974 Official Language Act (Bill 22) addressed this issue by making French the official language of Quebec and, by default, of Quebec’s schools. English-language education was to be reserved for English speakers; new arrivals to Quebec would have to pass a written language test to determine their eligibility to attend school in English. The Act was widely unpopular, particularly for the arbitrary nature of the testing process. It also undermined the long-standing reliance of Protestant boards and, to an extent, of English Catholic sectors on immigrants to maintain numbers.

The election of the Parti Québecois as the new provincial government in 1976 brought an end to the arbitrariness of Bill 22, which was replaced the following year with Bill 101, the Charter of the French Language. This new legislation was much clearer on the question of rights: children could attend school in English if their parents had received the majority of their education in English – in Canada, but not Britain, the United States or any other English-speaking country. Those who did not meet these qualifications would be obliged to go to school in French.

Although this arrangement was immediately opposed for infringing on basic educational rights, the Charter did for the first time establish the notion that Quebec Anglophones had a right to be educated in English, even if others did not. This “right” was not supported by any constitutional guarantees, however, and so was more properly a privilege granted by the majority. Indeed, at no point since then has the Parti Québécois not acknowledged the right of Anglophones to an English education (although its definition of what constitutes an “Anglophone” differs from that of many Anglophones). Nor in the long march towards the creation of linguistic school boards has the party deviated from its assumption that there should be English boards alongside French ones. Critics, however, point to the fact that the English school system, deprived of immigrants as a way to maintain numbers, is doomed to continue shrinking.

Ironically, the Charter has done much to unite an English-speaking population historically divided along religious and cultural lines. Arguably Anglophones have formed a distinct group since 1977, with the certificate of eligibility serving as a kind of membership card. There are many grey areas to this sense of unity, however, beginning with the position of so-called Allophones, many of whom still identify with English culture (read, perhaps, North American culture) despite having had all their education in French.

Increasing numbers of Anglophones, moreover, send their children to French school in the belief that it is the best way for them to learn French. Most curious is the degree to which Francophones with one “eligible” parent are exercising their right to attend school in English; in some parts of the province the majority of students in English schools speak French at home. Identity is rarely something one can acquire with a piece of paper.

Sources

Roderick MacLeod and Mary Anne Poutanen, A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998, Montreal, 2004.

The Quebec Home and School News.

School Board Archives across Quebec.

To Learn More

Charter of the French Language: http://canlii.ca/en/qc/laws/stat/rsq-c-c-11/latest/rsq-c-c-11.html

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.