Grandmother’s Bracelet

Organization: Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network

Coordinates: www.qahn.org

Address: Suite 400, 257 Queen St, Sherbrooke, QC J1M 1K7

Region: Estrie

Contact: Matthew Farfan for information execdir [at] qahn.org

Description: Small silver bracelet owned by Mary Cecilia Sheehan, enameled, now owned by Heather Davis. Photo 4: Heather Davis with bracelet and her 2012 carte blanche prize from the Quebec Writers’ Federation.

Year made: circa 1950s

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Sterling silver, enamel

Colours: Silver, blue

Provenance: Unknown

Size: 6.5 cm diameter x .9 cm wide

Photos: Rachel Garber

Mae’s 1950’s Bangle

Heather Davis

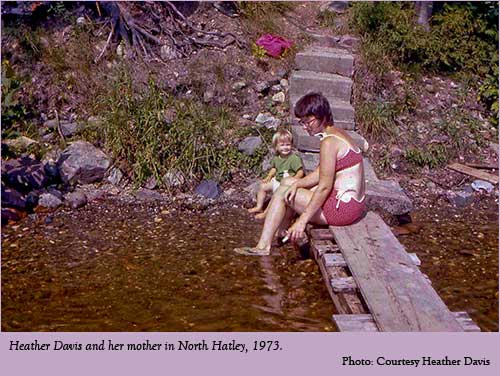

This is my grandmother’s bracelet. It’s sterling silver with vivid blue stripes and a solid clasp. My mother passed it on to me last year and it is the only thing I have that belonged to Mae. My grandmother’s real name was Mary Cecilia Sheehan and she was born on July 26, 1900. My family left Montreal for Vancouver when I was three, so I didn’t get to spend much time with her, but she did come out to visit our North Vancouver house twice.

The bracelet is quite small, but I hold it in my hand and admire it and wonder.

I was seven when she died.

Twelve years ago, I came back to Quebec. I’ve always felt like a real West Coaster, but since moving back to Quebec, I’ve found traces of my family in surprising places.

Mae married my grandfather, Paul-Gilles Gauthier, in 1922. He was an engineer, recently graduated from McGill, and he found work in the Lac St. Jean region. Mae didn’t speak much French.

The lady who lived above the young couple had been the inspiration for Maria Chapdelaine in Louis Hemon’s famous novel. She signed the front of a photograph and gave it to my grandmother. My mother showed me the photograph. My husband and I took the photo to a small museum in Lac St. Jean where we were told that the lady was Eva Bouchard. The lady at the museum had a signed photo just like ours.

When I came to Quebec and we lived in Drummondville, I thought of Mae and wondered how she survived the isolation. People were friendly with me, but learning French was a long process. I didn’t understand the way most people spoke. I didn’t understand when I took the dogs for a walk and somebody said, ‘Beaux pitous!”

Now 12 years later, I can understand a lot and say most of what I want to say. I hold the bracelet in my hand and wonder at its simple sturdy beauty and I wonder about how things come full circle. Me, the only real Westerner in my family, living in Quebec. But life is so different now. I find I am appreciated for my ability to teach the English language. People admire my efforts to learn and speak French. They like my accent. They ask me what nationality I am. They ask me how to pronounce my name. I tell them it’s a flower. They call me Heater.

They ask me why I left Vancouver to come live in Quebec because most of them want to leave Quebec to live in Banff or Whistler or Victoria.

I tell them that there’s something familiar about Quebec, that I feel at home here. I tell them that my daughter is growing up speaking both French and English and I’m jealous. I tell them that I like the distinct seasons, apple picking in the fall and the brightness of the snow in the winter.

Back to my grandmother, let me present a scene. My mother, in her Catholic school uniform, is eating in the kitchen. Her strict Quebecois father is eating in the dining room, reading the paper. Mae is wearing an apron and preparing everyone’s breakfast. My mother’s oldest sister, still unmarried and therefore forced to live at home, comes downstairs before heading off to work at “the Bell.”

Mae brings her a plate with her usual, a poached egg on toast. My mother stares at her sister whom she secretly calls “Miss Moody Sourpuss.” Ms. Sourpuss sticks her fork into the egg and hears a clinking sound. She drops her fork, speechless. The egg is not an egg. It is a white doorknob that Mae laid carefully on the toast.

Mae laughs and laughs. She howls. She loves to laugh. Later when everyone leaves, she goes to have her bath and puts on her elastic stockings. Perhaps she puts on her bracelet. It’s a gift from Gilles, a symbol of how much easier life is now that six of their seven children are grown up, now that Gilles has his own business and they have a little extra money.

My mother says my grandmother loved to sing while doing housework. She would sing Toura, Loura, Loura. At the time, my mother thought Mae was making up the words, but years later, at a cancer relaxation session, the music therapist sang the same Irish lullaby. I like to think it was Mae’s way of comforting my mother from afar.

The bracelet reminds me of where I came from. The bracelet reminds me of Mae, who howled when she laughed. I also like to laugh and laugh. All my friends will tell you so. The bracelet reminds me of myself.

About Going, and Coming

My family weren’t the only Anglophones to leave Quebec. Based on mother tongue census data, Marmen & Corbeil (2004) concluded that “The proportion of Anglophones has declined continuously, dropping from 14% in 1951 to 8% in 2001. This has resulted largely from the English mother tongue population leaving Quebec to live in other provinces, particularly during the 1970s. It is Anglophones at the peak of their working age who are most likely to leave their province of birth.”

Salée observed that the impression held by non-Francophones and new Quebecers is that “they are strangers in their own house.” In his words, “They are invited to partake in la nation Québécoise but according to terms and parameters upon which they have little or no control. They can be in the nation, if they wish; somehow, they will never really be of the nation” (Salée, 1977, p. 9).

Many arrive in Quebec, like I did, eager to learn and practice our French skills. As Gerald Cutting of Townshippers’ Association recently stated, “The language of the majority of Quebec residents is French, and Bill 101 reinforces the requirement of the use of the French language in public life. This reality helps to explain why ever-increasing numbers of English-speaking Townshippers are now bilingual, and why the census figures of 2011 show that the number of English speakers in our region has remained stable since the last report.”

In fact, the 2011 census data shows that 13.5% of the population of Quebec speak English as their first language (1,058,250 people).

Sources

Statistics Canada, 2011 Census, http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/prof/details/pa...

Townshippers' Association, Townshippers’ Telegram; Holiday Edition, December 2012, Page 4. http://www.townshippers.qc.ca/news/townshippers-association-president-on...

W. Floch, and J. Pocock, "The Socio-Economic Status of English-Speaking: Those who Left and Those who Stayed," In R. Y. Bourhis (Ed.) The Vitality of the English-Speaking Communities of Quebec: From Community Decline to Revival. Montreal, Quebec: CEETUM, Université de Montréal, 2008.

To Learn More

Ronald Rudin, The Forgotten Quebecers: A History of English-Speaking Quebec, 1759-1980, 1984.

“58 per cent of anglophones feel welcome in Quebec: poll,” http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2013/02/19/quebec-ekos-poll...

Garth Stevenson, English Speaking Quebec: A Political History, Quebec: State and Society, 2004.

Jack Jedwab, “Unpacking the Diversity of Quebec Anglophones,”: Community Health and Social Services Network, 2006. http://www.chssn.org/En/pdf/AngloDiversity_JackJedwab.pdf.

Jack Jedwab, “Going Forward: The Evolution of Quebec's English-Speaking Community,”: Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, Government of Canada, 2004. http://www.ocol-clo.gc.ca/docs/e/jedwab_e.pdf.

Author

Heather Davis is a writer who lives in Sherbrooke with her husband and daughter. She also teaches at the Université de Sherbrooke. In 2012, she won the 3 Macs carte blanche prize for her story, Aria, published in the Quebec Writers' Federation's literary journal.