Hugh Allan’s Bookcase/Mantlepiece

Organization: McGill University Hospital Centre

Coordinates: www.muhc.ca/pfv/rvh/

Address: 1025 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, QC H3A 1A1

Region: Montreal

Contact: Karine Raynor, karine.raynor(a)muhc.mcgill.ca

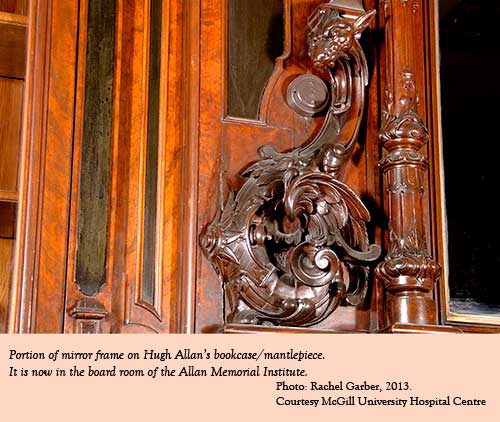

Description: Ornate wooden library bookcase and mantelpiece with many carved figures framing a huge mirror, that was once part of Sir Hugh Allan's Ravenscrag home and is now in the Allan Memorial Institute’s boardroom.

Year made: 1861

Made by: George Roberts

Materials/Medium: mahogany, glass

Colours: Dark brown

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 6.34 m wide x 4 m high x 66 cm deep

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy McGill University Hospital Centre

Ravenscrag: The Allan Memorial

Rod MacLeod

In the 1850s, wealthy Anglophone Montrealers began to build grand houses for themselves on the slopes of Mount Royal, forging a neighbourhood that would later be known as the “Square Mile” and even the “Golden Square Mile.” One of the choicest locations in the area was McTavish Street, which flanked the McGill University campus and the city’s new reservoir, both of which had been tastefully landscaped by 1860.

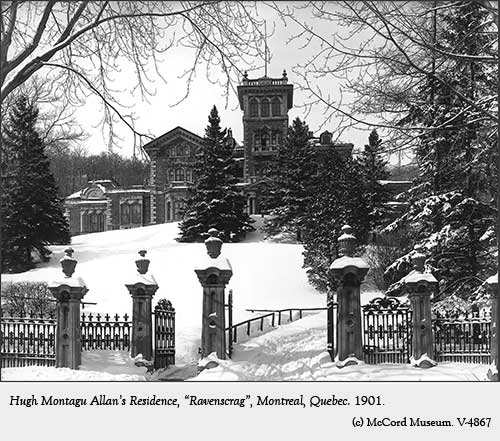

After purchasing a vast stretch of land at the top of the street, Hugh Allan decided to build a mansion for himself and his family overlooking the parkland and the city below. “Ravenscrag” was the grandest home in the city – arguably the grandest in the country – and would ultimately come to serve the larger community in unexpected ways.

A teenaged Hugh Allan arrived in Canada from Scotland in 1826, representing his father’s lucrative Greenock-based shipping business. Using family money, Allan acquired ships and established trade routes, not only across the Atlantic but far up the St. Lawrence River. By 1856, his consortium, the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company (aka the “Allan Line”), secured the government contract to provide regular transatlantic steamship service. Allan also invested heavily in rail transportation, and by the 1870s was one of the powers behind the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Banking, insurance, industry and natural resources were all domains upon which Allan made his substantial mark.

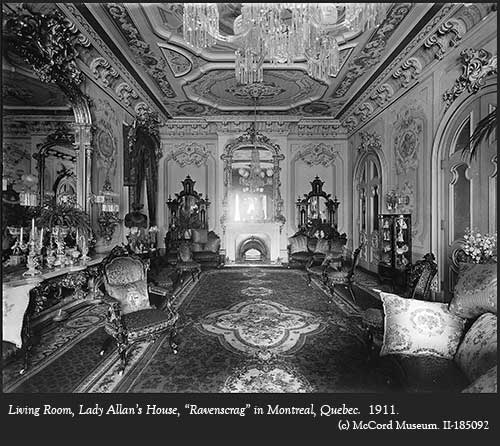

Several leading architects worked to design and build Ravenscrag in the 1860s, including Victor Roy, John William Hopkins, William Spier, and Alexander Fowler. This Tuscan Villa style mansion featured 34 rooms – including a complex of ballrooms, a billiard room, a conservatory and a library – all lavishly decorated with the plushest materials and the finest craftsmanship.  The library, reputedly Allan’s favourite room, boasted a vast, ornate mahogany bookcase festooned with carved figures framing a huge gilt mirror. In keeping with Allan’s origins with shipping, the mansion was crowned with a 75-foot tower that afforded a magnificent view over the St. Lawrence River valley. There was more than enough space for the Allans’ 12 children and the many servants attending them. Next to the mansion were the stables, housed in a separate building nearly as grand as Ravenscrag itself; its façade sported a carved horse’s head over the doorway. The mansion’s extensive grounds were surrounded by a heavy wrought-iron fence; access was via a massive gate, controlled by a gatekeeper who lived with his family in an adjacent house.

The library, reputedly Allan’s favourite room, boasted a vast, ornate mahogany bookcase festooned with carved figures framing a huge gilt mirror. In keeping with Allan’s origins with shipping, the mansion was crowned with a 75-foot tower that afforded a magnificent view over the St. Lawrence River valley. There was more than enough space for the Allans’ 12 children and the many servants attending them. Next to the mansion were the stables, housed in a separate building nearly as grand as Ravenscrag itself; its façade sported a carved horse’s head over the doorway. The mansion’s extensive grounds were surrounded by a heavy wrought-iron fence; access was via a massive gate, controlled by a gatekeeper who lived with his family in an adjacent house.

Hugh Allan died in late 1882, a year and a half after his wife Matilda Smith. Four unmarried siblings continued to live in the mansion, although in 1893 the second son, Montague, married Marguerite Mackenzie and eventually inherited his father’s mantle as lord of Ravenscrag. As was the case in many second-generation Square Mile residents, Montague surpassed his father in his lavish lifestyle. He expanded the mansion significantly, and regularly entertained governors-general and foreign dignitaries at soirées in Ravenscrag’s ballrooms. An avid sportsman, Montague filled his stables with thoroughbred horses and sponsored amateur hockey championships; the Allan Cup was his creation. He and Marguerite had four children, whose pampered upbringings were attended to by a dozen or more servants, as well as the coachman and gardener who also lived on the premises.

This idyllic existence was shattered in May 1915, when Marguerite and her two youngest daughters Anna and Gwendolyn set sail for England – on the Lusitania. The ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat, and although Marguerite, who was injured, was rescued, both girls drowned. Two years later, the Allans’ only son, Hugh, was killed in action over the English Chanel. Joy and festivity ended at Ravenscrag. The post-war depression obliged even the Allans to economize, although they hung onto their mansion longer than many of their peers did.

The remaining Allan daughter, Martha, was a non-conformist spirit, seemingly determined to break out of the confines of her privileged youth. Before the war she studied acting in Paris, and after a stint as a volunteer nurse in France she became a radio personality and theatrical impresario in California. Back home in the late 1920s, she set up her headquarters in the stables at Ravenscrag (the horses had long been sold off) and used her family connections to promote the arts. She organized a famous gathering of Montreal theatre lovers at which famed stage director Barry Jackson from Birmingham, England, promoted the idea of starting a community theatre company; this led to the founding of the Theatre Guild of Montreal, later the Montreal Repertory Theatre (MRT), where budding Canadian actors would cut their theatrical teeth under Martha Allan’s careful direction, often rehearsing in the Ravenscrag stables. (The MRT would later be home to such notables as Christopher Plummer, Hume Cronyn and John Colicos.) Martha also helped establish the Dominion Drama Festival, an annual ceremony that gave awards for achievement in community theatre.

Alas, in 1942, after a sudden illness, she died at the age of 45.

Montague and Marguerite Allan, now in their 80s, had long since vacated Ravenscrag for the Chateau Apartments on nearby Sherbrooke Street. With Martha gone, they wished to be rid of their mountain mansion and all its memories. Rather than sell it, however, they opted to donate the entire property to the Royal Victoria Hospital, an act that spared Ravenscrag from the demolition and redevelopment that has been the typical fate of Square Mile homes. McGill University, to which the RVH was by then affiliated, decided to install its new Institute of Psychiatry in the building, renaming it the Allan Memorial Institute – the “memorial” referring to the four siblings who had died before their parents.

The transition to psychiatric hospital in 1943 meant covering up the mansion’s interior fixtures. The exterior – mansion, stables, gates and gatehouse – was preserved almost intact, and the tower still affords a stunning view, but ballrooms, dining room, drawing room and breakfast room were all subdivided into smaller quarters for offices, treatment centres and patient bedrooms. Hallways and stairwells are now, inevitably, plain and institutional.

One of the few rooms to retain its original dimensions was Hugh Allan’s beloved library, now used for board meetings. The ornate mahogany bookcase is the only remaining echo of the glory that was Ravenscrag.

Sources

www.arch.mcgill.ca/prof/adams/arch533/summer2012/allan.html

John Kalbfleisch, “Shipping heiress kept theatre alive in Montreal,” Montreal Gazette, March 29, 2009.

François Rémillard and Brian Merrett, Mansions of the Golden Square Mile, Montreal, 1850-1930, Montreal, 1987.

Brian Young and Gerald Tulchinsky, “Hugh Allan,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography On-Line.

To Learn More

Donald MacKay, The Square Mile, Merchant Princes of Montreal, 1987.

Margaret W. Westley, Remembrance of Grandeur: The Anglo-Protestant Elite of Montreal, 1900-1950, 1990.

Terry Neville, The Royal Vic: The Story of Montreal`s Royal Victoria Hospital, 1994.

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.