Iroquois War Club

Organization: Stewart Museum

Coordinates: http://www.stewart-museum.org

Address: 20 chemin du Tour-de-l’Isle, Montreal, QC H3C 0K7

Region: Montreal

Contact: Sylvie Dauphin, info(a)stewart-museum.org

Description: A carved and polished curved stick with a ball at the end used by Iroquois warriors in warfare during the 18th century.

Year made: mid-18th century

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Wood

Colours: Brown

Provenance: Quebec or upstate New York

Size: approximately 63 cm x 8 cm

Photos: Courtesy Musée Stewart Museum

The Iroquois War Club

Rod MacLeod

Schoolbook histories have long presented the stereotype of the Iroquois as warlike foes of early French settlers rather than as players in a complex story of economic and political interaction with other peoples in a colonial structure. Arguably, as an agricultural people, the Iroquois resisted European encroachment more determinedly than other Amerindians in the northeast, and with better organization. The main antagonists until 1701 were French; the history of French relations with the Iroquois is largely one of conflict, except with the Catholic minority who accepted the colonizing agenda and settled close to them at old Iroquoian sites on the St. Lawrence River. Earlier alliances between the Iroquois and the British came back into play once New France became British North America. In this context within what is now Quebec, the British (and then Canadian) government laid claim to these Iroquois lands, and the outside language the Iroquois came to utilize most was English.

Contact with the French eventually led some Mohawk (the easternmost of the five nations making up the Iroquois Confederacy) to convert to Catholicism and form communities in New France. One of these, Kahnawake, lay on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River near Montreal, and was a Jesuit mission; another, Kanehsatake, was established on the north shore of Lake of Two Mountains as a Sulpician mission. Both religious orders were the seigneurs of their respective lands. After the conquest of New France, Jesuit property was eventually reallocated but the politically astute Sulpicians and their lands were left intact. In 1762, the residents of Kahnawake petitioned the British governor, reminding him that the Iroquois had signed the Treaty of Kahnawake as an independent nation after the Seven Years’ War. Consequently, the governor granted them the title to the former mission lands. During the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the Mohawk of Kahnawake sided with the British. The provisions of the 1774 Quebec Act guaranteeing Catholic religious and civil rights concerned the residents of Kahnawake, for whom Catholicism remained the official religion.

The residents of Kanehsatake had much less reason than their counterparts south of the river to support British interests, particularly given the government’s willingness to enforce the Sulpicians’ rights as landowners. Mohawk claims were repeatedly rejected by the courts; in 1841 a special ordinance even confirmed Sulpicians’ seigneurial title. Confident in their legal position, the landowners began to make life as hard as possible for the Mohawk community, and as embattled residents fled elsewhere, the Sulpicians encouraged French-Canadians to settle on their land. Mohawk who stayed responded to this treatment by deliberately flaunting seigneurial privilege by cutting trees for firewood on land that already belonged to them and opening new lots, both punishable offences. They also left the Roman Catholic church. Numbers of Mohawks converted to Protestantism and followed the Methodist missionaries active in the area, but most simply stayed away from both churches. In 1868 the Sulpicians appointed Joseph Onasakenrat as secretary to the head of their Lake of Two Mountains mission; they had subsidized the education of this promising young Mohawk at the Montreal seminary. Soon however, Onasakenrat was elected chief at Kanehsatake and began to champion the people's cause, denouncing the landowners’ claims. The Sulpicians had him arrested and ordered the dismantling of the Methodist chapel whose congregation Onasakenrat had joined (and would later lead as an ordained minister). While imprisoned, Onasakenrat translated part of the New Testament into Mohawk; his work was published in 1880. The following year, the Sulpicians’ mission church in the village of Oka burned down, leading to accusations of arson which were only dropped years later.

The question of native land claims is a vital one across North America, and the issue is uniquely complex in Quebec. The Iroquois figure prominently in Canadian history as the antagonists of the French. One of the Iroquois nations, the Mohawk, have played a significant role in Quebec over the past three and a half centuries, particularly in the communities of Kahnawake, Kanehsatake and Akwesasne. Having become allies of the British and today using English more than French, these Mohawk communities have a unique position within Quebec society.

Sources

Olive Patricia Dickason, Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, Toronto, 1992

Donald B Smith,“Joseph Onasakenrat,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography On-Line

To Learn More

Bruce Trigger, Natives and Newcomers: Canada's Heroic Age Reconsidered, 1985.

William N. Fenton, “The Iroquois in History,” North American Indians in Historical Perspective, 1971.

Handbook of North American Indians ed. W.C. Sturtevant and Bruce Trigger, volume 15 “Northeast,” 1978.

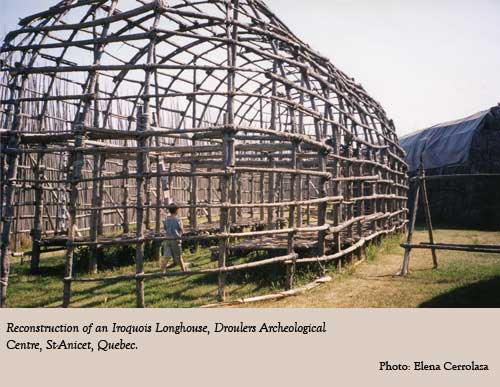

People of the Longhouse http://www.civilisations.ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/fp/fpz3d_1e.shtml

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.

Consultant

Roy Wright is a professor of First Peoples Studies at Concordia University