James McGill Monument

Organization: McGill University Archives

Coordinates: www.archives.mcgill.ca

Address: 3459 McTavish Street, Room M6-17B, Montreal, QC H3A 0C9

Region: Montreal

Contact: Gordon Burr. Gordon.burr(a)mcgill.ca

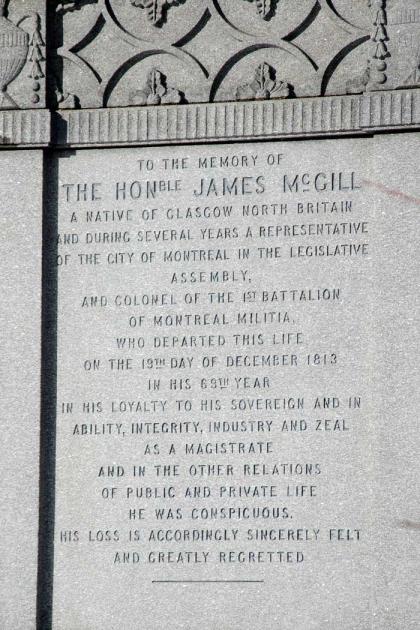

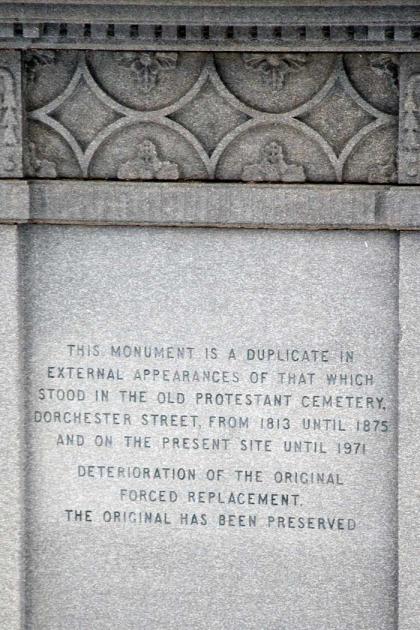

Description: A four-sided stone pedestal topped with a decorative urn in memory of the Honourable James McGill, founder of McGill University. It bears the inscription: “To the Memory of the Honorable James McGill a native of Glasgow north Britain and during several years a representative of the City of Montreal in the Legislative Assembly, and Colonel of the 1st Battalion of Montreal militia, who departed this life on the 19th day of December 1813 in his 69th year. In his loyalty to his Sovereign and in ability, integrity, industry and zeal as a Magistrate and in other relations of public and private life he was conspicuous. His loss is accordingly sincerely felt and greatly regretted.” Also: “This monument and the remains which it covers were removed from the old Protestant cemetery Dorchester Street, and placed here in grateful remembrance of the founder of this university, 23rd June 1875.”

Year made: 1813-1814

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Granite

Colours: Grey

Provenance: Quebec

Size: Approx. 2.5 m tall x 1 m x 1 m

Photos: Rachel Garber

James McGill’s University

Rod MacLeod

No last will and testament had more significance for Quebec’s Anglophone population (and arguably for Canada) than James McGill’s, drawn up in 1811, two years before his death. McGill was a leading Montreal merchant, a member of the legislative assembly, a justice of the peace, and a mover and shaker in every civic enterprise from dismantling the city walls to founding the Protestant cemetery. Yet, like the Scottish lord in Macbeth, nothing became McGill’s life like the leaving of it. Today, McGill is a name known around the world, thanks to a university that has capitalized on the image of the “founder” in a savvy way.

The enterprise was touch-and-go from the beginning. James McGill wanted to encourage public education, and so left his farm (“Burnside”) northwest of Montreal to the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning. This body had been created a decade earlier to open public schools in Lower Canada, a mandate it had not been fulfilling very effectively so far. McGill wanted the Royal Institution to create a university, one college of which would be located on the Burnside farm and bear McGill’s name. He also left £10,000 for maintenance.

McGill’s own heirs were well provided for, especially his stepson, François Desrivières, whose father had been a prominent fur trader. Even so, knowing that the Royal Institution still had no kind of governance structure and might take some time to act on his bequest, McGill added a proviso in his will that, until a college was built, his widow and heirs could make use of Burnside. Furthermore, if no college were built within ten years, both land and cash would go to Desrivières.

Once the Royal Institution had acquired a board of trustees in 1819, McGill’s executors asked Desrivières to vacate the farm. He refused, stating that the proviso in his step-father’s will had clearly not been met. Two years later, the executors transferred the title deed for Burnside to the Royal Institution, whose trustees arranged for a charter for “McGill College.” The university would later place great stock in its “founding” date of 1821, but there were still no students or teachers. Certainly Desrivières was not impressed by the charter, and refused to vacate, let alone surrender his claim to the £10,000.

The trustees were obliged to take legal action, strongly admonishing Desrivières for dishonouring James McGill’s legacy. The legal battle that ensued pitted the Anglo-Protestant establishment against Desrivières, who found himself a symbol of French Catholic opposition to what was perceived as a Protestant drive for public education. In the end, the Royal Institution won the case, and the Desrivières family were nearly wiped out financially, liquidating their assets to pay off the accumulated interest on the £10,000.

Because of this interminable legal battle, it was only by the late 1830s that the Royal Institution began to see any of the money McGill had left it. A competition was held for a design for a college building. The winner was the young English architect John Ostell, who had already built the new Customs House (today part of the Pointe-à-Callière Museum) and would go on to have a lucrative career as a surveyor and industrialist.

After many delays, a partly-completed Arts Building was ready to receive students by September 1843 – three students, in fact. Numbers rose in subsequent years, but until the early 1850s there was little enthusiasm for the benefits of an Arts degree. At this time, “Arts” meant everything but medicine; for some years the college had been granting medical degrees to students who had trained with doctors at the Montreal Medical Institution, but this was a matter of rubber stamping decisions over which the college had no real authority.)

McGill University only came into its own after the arrival of Nova Scotia geologist John William Dawson as principal in 1855. Dawson presided over the transformation of the college from essentially an elite private school into a serious modern institution of higher learning.

He also began the tradition (which has served McGill well ever since) of securing the financial support of men with very deep pockets: men such as William Molson, who paid for the completion of the Arts Building and the landscaping of the Burnside grounds as a campus, and later Peter Redpath (of the eponymous library and museum) and William Christopher Macdonald (of the science and engineering buildings that bear his name). The involvement of such men did much to convince Montrealers – and increasingly people from further afield – that McGill was an institution worthy of their sons’ attendance. After 1884, thanks to a major donation from yet another rich man, Donald Smith, McGill became an institution that young ladies could attend as well.

Dawson also presided over the creation of a Normal School, which would train Quebec teachers for generations under McGill’s wing, and the development of the High School of Montreal as a modern secondary institution, later absorbed into the public school system. The hand of McGill also spread across the province as other aspiring institutions of higher learning sought affiliation so that their students might obtain advanced degrees: St. Francis College in Richmond and Morrin College in Quebec City are the key examples. In the early twentieth century, Macdonald funded the creation of an agricultural college in St. Anne de Bellevue, which taught scientific farming under the McGill flag.

Meanwhile, the original donor, James McGill himself, was lying peacefully in the Protestant Burial Ground he had helped to establish. In the early 1870s, however, the city wished to expropriate this ground for a park, and encouraged families whose loved ones were buried there to have their remains removed to the new Mount Royal Cemetery on the Mountain.

The college governors (successors to the Royal Institution trustees) hit upon the idea of having the founder reinterred on the campus, and obtained permission from McGill’s heirs (ironically, the Desrivières family) to move him. A spot of ground situated right in front of the Arts Building was consecrated by the Anglican bishop, and on 23 June 1875 the founder was reinterred in the heart of the university he had, more or less, launched into existence. For the occasion, the Canadian Illustrated News (29 May) featured an engraving of the McGill Campus, reflecting an only slightly fanciful vision of this elegant institution.

Soon after, official McGill songs emerged to express the pride alumni felt for their founder:

James McGill, James, McGill,

Peacefully he slumbers there,

Blissful, though we’re on the tear.

James McGill, James McGill,

He’s our father, oh yes, rather,

James McGill!

In more recent years, the campus has been adorned with a plaque marking the site of the “Founder’s Elm,” which James McGill himself supposedly planted but which did not survive the spread of Dutch elm disease in the 1970s. In 1996 a whimsical bronze statue of the founder by David Roper-Curzon was placed on the lower campus, showing McGill striding determinedly forward.

Sources

Stanley Brice Frost, McGill University for the Advancement of Learning, 1980/84.

McGill University Archives, RG.4.

To Learn More

Paul Axelrod, "McGill University on the Landscape of Canadian Higher Education: Historical Reflections." Higher Education Perspectives 1 1996–1997.

Margaret Gillet, We Walked Very Warily: A History of Women at McGill, 1981.

Stanley Brice Frost, James McGill of Montreal, 1995.

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.