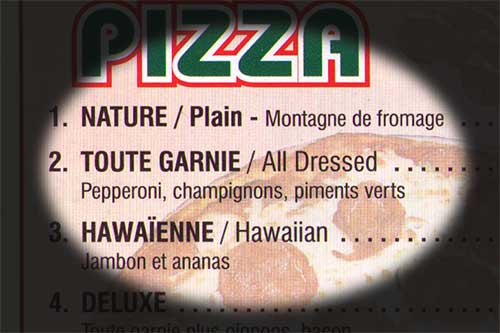

Montreal Pool Room Sign

Organization: Montreal Pool Room

Address: 1217 St. Laurent Boulevard, Montreal, QC H2X 2S6

Region: Montreal

Contact: Deniz Hadjiev, 514-506-0330

Description: The large sign of a restaurant that has become a familiar landmark. It stayed in the same block of the Lower Main even after a fire in 1989 forced it to move across the street.

Year restaurant opened: 1912. Year sign was created: 2012

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Metal, wood, glass, plastic, paint

Colours: Red, white, black, yellow, green, etc.

Provenance: Montreal

Size: Approx. 6 m x 1 m

Photos: Rachel Garber

Montreal Pool Room

Mark Abley

In the lower reaches of a long street that Montreal’s English speakers have learned to call “Boulevard Saint-Laurent” and French speakers sometimes refer to as “la Main,” you’ll find a restaurant that opened its doors in 1912 and is still serving such down-to-earth delicacies as Hot Dog Steamé, Hot Dog Toasté, and Michigan (a steamed hot dog with a meaty sauce). The Montreal Pool Room is located just down the street from a music venue named Club Soda, and across the road from Café Cléopatre and its “strip-teaseuses.” If you want your steamie to come with chopped onions and cabbage, ask for it “all dressed.” You can munch it while sitting at a metal counter below a signed photograph of Patrick Roy, near a framed map of “Le West Island.” The décor is half austere, half kétaine.

The unofficial mixture of languages that the Montreal Pool Room incarnates is nothing that would delight the inspectors of l’Office québécois de la langue française. “Poutine” may have become accepted as a pure laine French term, despite its probable origins in the English noun “pudding,” but “le cheese burger” hardly counts as standard French. The clientele of the restaurant don’t appear to mind. The French they speak is dotted with English, the English they speak is dotted with French: a rough-and-ready, grizzled embodiment of the bilingual city they share.

Montreal English is a unique dialect for several reasons. Compared with how the language is spoken elsewhere in Canada, it shows an unusual degree of Yiddish influence: you don’t have to be Jewish here to use expressions like “schlep” and “mensch” and “Enough already!” In the neighbourhood of St. Léonard – always pronounced, in Montreal English, so as to rhyme with “leotard” – the widespread Italian presence affects the cadences and pronunciation of English. But the dominant influence on the English spoken throughout the city, indeed the whole province, is French.

Look at the first two paragraphs of this essay. Throughout the world, English speakers rely on such French-derived terms as “restaurant,” “delight,” “décor,” “boulevard,” “venue” and “clientele.” But only in Quebec do English speakers casually use words and phrases like “steamie,” “pure laine,” “all dressed” and “kétaine.” The influence of the French language is most obvious on the level of vocabulary, yet it has a subtle impact on grammar too. Children come home from English-language schools and tell their parents that they scored “eight on ten” on a math test – a direct translation of “huit sur dix.” In other parts of North America, “eight out of ten” is standard.

The most famous example of French influence, of course, is the word “depanneur,” often shortened to “dep.” Purists, I realize, would add an acute accent, spelling the word “dépanneur” – but when Montrealers speak English, the first syllable of that word always rhymes with “step,” not “shape.” Other French-derived expressions that suggest a working-class experience are “three and a half” (an apartment with three rooms plus a bathroom), “caisse pop” (few if any Quebecers would talk about a credit union) and “gallery,” in the sense of porch. Mind you, on the Lower North Shore, where the rich and salty dialect of Newfoundland exerts a gravitational pull, a porch is often called a “bridge.”

Increasingly, though, Quebec English has a bourgeois feel. In the 21st century much of its linguistic code-switching and borrowing reflects the political power and social prestige of French. Let’s suppose that after enjoying the vin d’honneur at a cinq à sept, you need an allongé before you reach the vernissage. (Habitués of the Montreal Pool Room might not recognize some of these idioms.) Less obvious than those direct borrowings are the many words and expressions that form part of standard English but are used more often, or differently, in Quebec. “Formation” instead of “training;” “dossier” rather than “file;” “permanence” in place of “tenure;” “consuming” drugs as opposed to “taking” them: the examples are legion. When the meanings of words in Quebec English diverge from those in the North American mainstream, as they sometimes do, is the discrepancy merely an error, or is it a sign of vibrant cultural difference?

I’ll leave it up to you to decide. Think of this as a communiqué, not an exposé.

To Learn More

Places of a Lifetime series, Traveler Magazine. National Geographic Travel. http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/places/places-of-a-lifetime/montrea...

Author

Mark Abley was born in England, grew up in western Canada, and has lived in the Montreal area since 1983. A Rhodes Scholar and a Guggenheim Fellow, he has written or edited more than a dozen books of poetry and prose.