Prisoner’s Graffiti

Organization: Morrin Centre

Coordinates: www.morrin.org

Address: 44 Chausseé des Écossais, Quebec City, QC G1R 4H3

Region: Quebec City Region

Contact: Maxime Chouinard, info(a)morrin.org

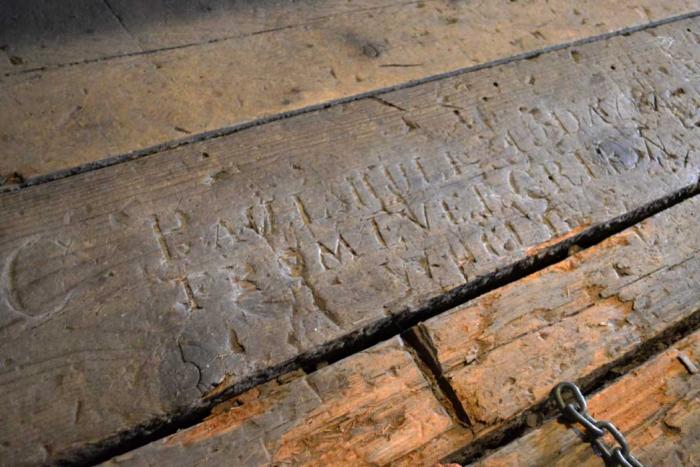

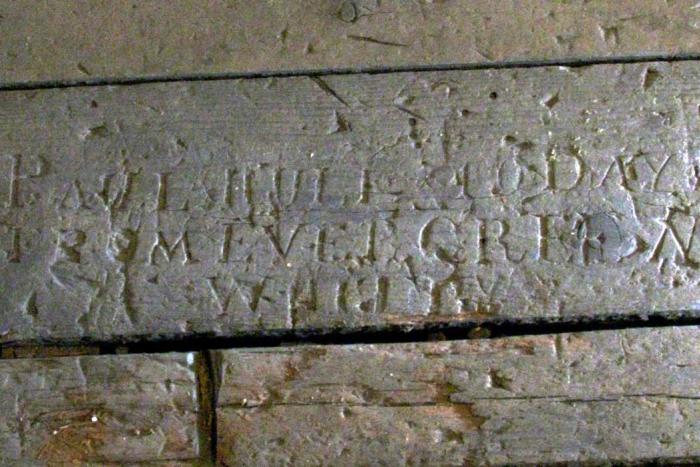

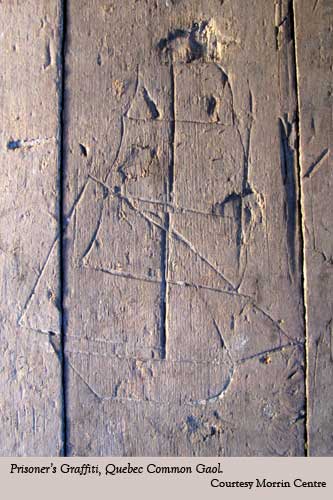

Description: Graffiti carved by English sailor Christopher Paul during his incarceration in the Quebec City common gaol in 1850, and chalk drawing by other prisoners.

Year made: 1850

Made by: Christopher Paul

Materials/Medium: carved or etched wood

Colours: Natural

Provenance: Quebec City

Size: Varied

Photos: (1-3) Courtesy Morrin Centre; (4) Rachel Garber.

Graffiti from the Quebec Common Gaol

Donald Fyson

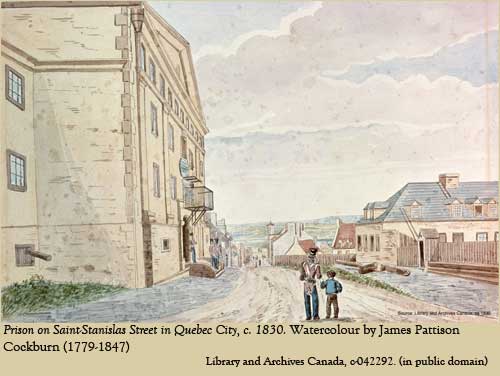

These graffiti come from the old Quebec City common gaol (pronounced "jail") on Saint-Stanislas Street. They were scratched or carved into the floorboards by prisoners: drawing ships or playing checkers was one way to pass the time! Christopher Paul's carved inscription made sure he would not be forgotten. He was a 22-year-old English sailor on the ship “Evergreen,” which arrived in Quebec City from London in May 1850.

Along with several crewmates, Paul refused to work, and the ship's captain, Benjamin Pearson, had them committed to gaol. Paul was sentenced to forty days, but was let out a month later, just as Evergreen was setting sail back to London with a load of timber.  It was probably Pearson who got Paul released, so that he wouldn't lose his crewman's labour. Two of Paul's crewmates were luckier - they managed to escape from the gaol and were never heard of again.

It was probably Pearson who got Paul released, so that he wouldn't lose his crewman's labour. Two of Paul's crewmates were luckier - they managed to escape from the gaol and were never heard of again.

Prison reform in Quebec

The Quebec common gaol was the city's main prison between 1812 and 1867. It was built between 1808 and 1812, as one of Quebec's first two "modern" prisons. The architect, François Baillairgé, followed the ideas of English prison reformer John Howard. Howard believed that prisoners should be separated according to their sex, their age, their crimes, and their criminal record. Hardened or dangerous criminals shouldn't be allowed to influence young first-timers who were in for minor offences.

As well, Howard thought that petty criminals should be put to hard labour, since work was supposed to bring moral reform. When they weren't working, prisoners should be locked up in individual cells. So Baillairgé divided the gaol up into different wards, each with a common central work space and lock-up cells around the outside for sleeping. It was meant to be a model prison.

From reform to reality

None of this worked very well in reality. The population of Quebec exploded during that period. As well, by the 1830s, imprisonment had become the favourite punishment for petty offences such as vagrancy and public drunkenness. The prison rapidly became overcrowded: there were sometimes over 200 prisoners in gaol at a time, twice what Baillairgé had planned for. Over 60,000 prisoners were locked up during the half-century the gaol was open.

There were also too many different types of prisoners to allow classification: from drunks and prostitutes to murderers and rapists, along with debtors (their creditors could put them in prison), and, of course, disobedient sailors. At best, criminals were separated from debtors, and women were separated from men. Even children as young as 10 or 12 might find themselves in gaol, for petty thefts or vagrancy, mixed in with the other prisoners. From 1829, female prisoners had their own separate building in the gaol compound, but that didn't stop men and women talking back and forth through the windows. Some prisoners were put to work, picking apart old hemp ropes to make caulking for ships, but others did nothing.

An Anglophone institution

Even though Quebec City always had a majority Francophone population, the gaol was a very Anglophone institution. Almost all of the staff were English-speaking. More importantly, almost three quarters of the prisoners were of British descent, and over half were of Irish origin. These were not the rich Anglophones of legend! This reminds us that cities like Quebec and Montreal had very large populations of poor Anglophones, mostly Irish, but also English and Scots.

Quebec City was also a major port, tied into the shipping trade between North America and Britain. Thousands of sailors, mostly British, arrived in port each summer; many stayed for the month or so it took load their ships with timber, Quebec City's main export. Some were put in gaol for drunkenness or rowdiness. Others deserted ship to stay in Quebec, or allowed themselves to be wooed away to another ship, in a practice known as “crimping.”

Problems, problems

Although it was initially praised as well-designed and modern, the gaol quickly became a dirty, smelly place. There was no running water until the mid-1850s, and the toilets were privies attached to the rear of the building. It was heated by wood stoves, and candles were used for most lighting. Along with the tobacco pipes that prisoners used, that made for a very smoky atmosphere. The thick stone walls and the stone and brick partitions inside also made it damp and chilly in winter, while the lack of ventilation meant that the upper floors baked in the summer.

Gaolers did their best to keep the place scrubbed clean and whitewashed, and surprisingly few prisoners died of diseases, but it must have been a very unpleasant place to be locked up in. And an ominous place as well - over the years, 16 men were hanged in front of the prison, most from an iron platform that jutted out over the main door.

The gaol also wasn't very secure. It was right in the heart of Quebec City, surrounded on all sides by streets, and easily accessible to passers-by. Liquor, tools and weapons went in the windows, and gaol blankets and gaol clothing came out as payment. As well, many prisoners tried to escape, and some were successful. Paul's crewmates were exercising in the tiny prison yard, when a guard opened the outside gate for a delivery. Seven men burst past the guard, and ran off down the street. Four were later caught, but not Paul's companions.

The end of the gaol

Right from the 1820s, there were calls for the gaol to be replaced. But the Saint-Stanislas gaol didn't close down until 1867, when the prisoners transferred to a new prison on the Plains of Abraham. The old building then served other purposes for Quebec City's English-speaking community. For a while it housed Morrin College, a university-level institution. It also became the home of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, which now runs the Morrin Centre, an Anglophone community organization and library.

Most of the cell blocks were torn down, but in the basement are the remains of two wards, initially used for criminals condemned to death and as punishment cells, and later as an overflow area during the busy summer months. That was where Christopher Paul carved his name, and you can still visit and see it today.

Sources

Maxime Chouinard with the assistance of Donald Fyson, Doing Time - Quebec City’s Common Gaol, 1808-1867, permanent exhibit at the Morrin Centre, Quebec City.

"New gaol exhibit at the Morrin Centre"

Donald Fyson, "Glimpses of Quebec City's Common Gaol, 1808-1867", Society Pages: The Magazine of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec 32(2011): 5-7.

Patrick Donovan, "Morrin Centre," in Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec: registers of the Quebec City common gaol from 1813 onwards http://www.banq.qc.ca/collections/genealogie/inst_recherche_ligne/instr_...

If you search for Christopher Paul, you'll see that he apparently claimed he was a 25-year-old from Canada, which English records show was not true.

To Learn More

John Howard, The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, with Preliminary Observations, and An Account of Some Foreign Prisons (Warrington: William Eyres, 1777).

George Fisher Russell Barker, "Howard, John (1726?-1790)", Dictionary of National Biography Volume 28

Tessa West, The Curious Mr. Howard: Legendary Prison Reformer (Hook: Waterside Press, 2011).

Author

Donald Fyson, professor at the Département d'histoire of Université Laval, is a specialist in 18th, 19th and 20th-century Quebec history. He is interested in the history of the law, of justice, of crime, of prisons, and of violence. He also studies the historical relations between different ethno-cultural groups in Quebec.