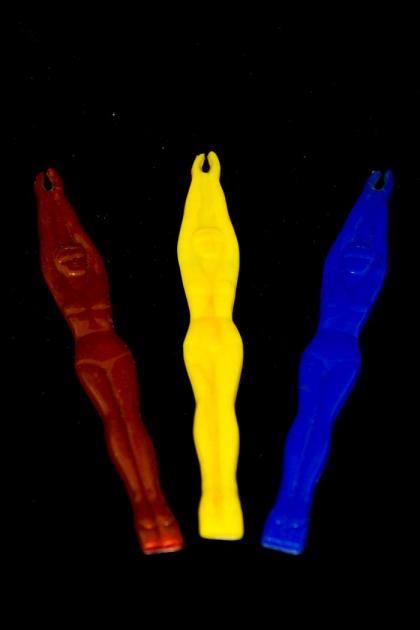

Swizzle Sticks, Rockhead’s Paradise

Organization: Concordia University Records Management and Archives

Coordinates: www.concordia.ca

Address: 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd., Montreal, QC H3G 1M8

Region: Montreal

Contact: Caroline Sigouin, archives(a)alcor.concordia.ca

Description: Three plastic swizzle sticks from Rockhead’s Paradise, each in the shape of a diving woman. “Rockhead’s” is written on the back. One is blue, one is red and one is yellow.

Year made: Unknown

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Plastic

Colours: Blue, red, and yellow

Provenance: Montreal

Size: 16.2 cm x 2 cm

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Concordia University and Rohinton Ghandhi

Rockhead’s Paradise Club – The House that Rockhead Built

Rohinton Ghandhi

Don't it always seem to go…That you don't know what you've got til it's gone…

They paved “Paradise” and put up a parking lot.

Standing in an empty parking lot at the corner of Mountain and St. Antoine was an eerie feeling.

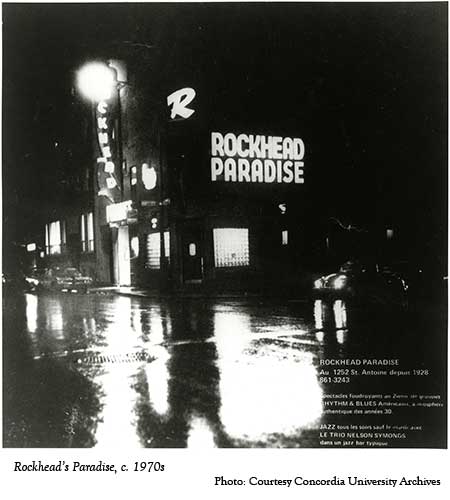

As swirls of dust danced across the asphalt on a cold winter’s day, it was almost as if he knew that we were there. For at that moment, we were centre-stage at what was once known as “the hippest place for jazz in the world.” It was a listed stop in Billboard magazine’s “Attraction Routes” for many entertainers and musicians touring through Montreal over several decades.

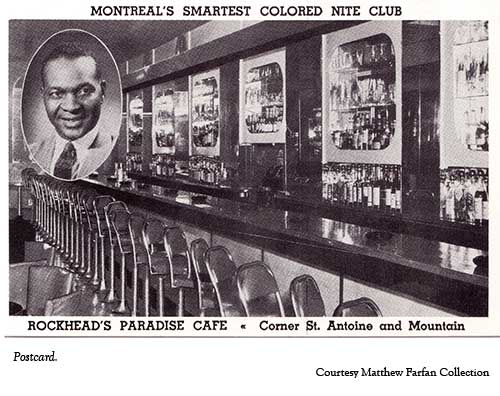

The club once boasted having the longest bar in the country at 23 metres (75 feet). Its owner had the distinction of being Montreal’s first Black nightclub owner, and possibly the first in Canada. With only his keen sense of knowing what the crowds wanted, his club showcased some of the most talented performers of his time. As we reopened the double doors of “The House that Rockhead Built” and walked into the smoke-filled nightclub world of Rufus Rockhead’s Paradise...

Setting the stage…

Rufus Nathaniel Rockhead was extremely secretive about his birth-date, even with his closest family and friends. His limited records show only that he was born in the year 1896 in Maroon Town, an independent territory in Jamaica. Like his father, John Rockhead, he came from a long line of “Maroons” who were the proud freedom-protectors against English rule. In early 1918, Rufus Rockhead immigrated to Halifax, Nova Scotia where his forefathers had helped build British military installations, and soon made his way to Montreal, Quebec. On January 29, 1918, he joined Canada’s Infantry as a private first-class with the 1st Depot Battalion of the 1st Quebec regiment at $15 per month. He served in France during WWI under the Canadian Forestry Corps, earned a British War Medal and a Victory Medal, and returned home a hero on March 19, 1919.

A snare-drum picks up a beat with the bass…

The Roaring Twenties brought in the wild times of prohibition, speakeasies, flappers and the earliest notes of jazz. At the time, Mr. Rockhead was already working as a porter for the CPR Railway, frequently running the Montreal-Windsor route and hopping over to Detroit to “make some real cabbage” during prohibition. In 1927, he left the CPR and setup a prosperous hat-cleaning and shoe-shine business in Verdun, Quebec. Later that year, a vintage photo stamped Plaza Studio (in New York City) showed a young Rockhead proudly standing beside his new bride Elizabeth (Bertie). Her long white wedding gown and “peacock” headdress fully complemented his black tuxedo, white gloves, and top hat, even then, revealing the one flower in his lapel. They had met at their local church and fell in love. Their union produced their three treasures, Jackie, Kenny, and Arvella.

A piano hammers in rhythm…

Rockhead always dreamed of owning a bar. In 1928, he applied for a beer permit, yet the commissioner replied, “You know we don’t give licenses to coloured people.” Rockhead persisted, and after 11 months of “pulling strings,” he became Montreal’s first Black citizen to hold a tavern license. He first tried purchasing a building on Bleury and St. Kit’s (St. Catherine Street) but was refused and reminded that “his place was not uptown, but downtown after the tracks.” Soon after, he purchased a three-storey building and opened a tavern on the corner of Mountain and St. Antoine, the very first street below the tracks.

Early in 1929, Rockhead added a lunch counter serving full-course meals for 25 cents, and opened a 15-room hotel on the uppermost floor. In October, the Crash of ’29 started the Great Depression but Rockhead was undeterred. In 1930, “Rockhead’s Paradise” club was officially opened, serving only wine and beer in its new second-floor dining room with a stage where local coloured jazz bands played.

A trumpet joins the group…

After a 5-year battle, Rockhead obtained his hard-liquor license and the Paradise became a cocktail bar. One year later, Quebec’s Premier Maurice Duplessis cancelled the licenses of ethnically-owned establishments, as a precursor to the 1937 Padlock Act. A now, well-experienced, well-connected, Rockhead knew just what to do and soon regained his license. The famous “Rockhead’s Paradise” neon sign soon lit-up the corner. Yet another law required that hotels have a separate entrance. Rockhead kept the street-level cocktail bar, remodelled the second floor into a nightclub, and converted the old hotel’s third floor into an upper dining area, complete with the famous “Stump’s Kitchen.” Half of this floor was completely cut-out so that patrons could watch the acts below from their perches above.

The band’s in full swing…

The 1940s were the club’s heydays, as the war brought in thirsty servicemen that were hungry for entertainment. Rockhead’s gave them big glittery shows, featuring comedians, acrobats, hoofers (tap-dancers), exotic-dancers, and a chorus-line called the “Rockhead-ettes.” The house band, Allan Wellman’s Orchestra, provided the music for many of these performers. Rockhead’s became as famous as the Cotton Club in New York’s Harlem and made Rufus a wealthy man. His nightclub featured many great Black performers including Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughn, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and two young Montrealers named Oscar Peterson and Charles Biddles. Rockhead welcomed all into his Paradise, without the race rules of the uptown clubs. He always wore a red flower in his lapel and handed a rose to each lady as she entered. In his club, Black and White musicians performed together freely, and all patrons enjoyed the jazz, no matter their race.

The players take 5…

In 1951, Rockhead brought his son Kenny (21) on board and spent $100,000 to double the club’s size and to install a new air conditioning system (complete with water tower). In 1952, with renovations completed, Rockhead refused to make a $40,000 “political contribution” to the Duplessis party. He offered half, which wasn’t enough to save his liquor license. Under a mocked-up charge of staying open after-hours, the club was padlocked with everything in place, all except $10,000 in alcohol which was never seen again. For the next 8 years, only the tavern paid the bills as the new Paradise rotted away next door, and with it Rockhead’s fortune. He sold an apartment building and two duplexes to avoid bankruptcy and was frequently seen sitting quietly on a stool outside his empty tavern on Mountain Street. Only a miracle could save his dream.

The bands return…

In 1960 that miracle came. With the Liberals in power, Rockhead’s was back. Re-opening the club was a surreal experience, with cobwebs stretching from ceiling to floor and with dust covering everything as it was in 1952. After being closed for so long, the place was practically forgotten. Montreal’s action-spot had shifted uptown and television was cutting into nightclub traffic. Although headliners like Redd Foxx, Nipsey Russell, Sammy Davis Jr. and Montreal musician Oliver Jones would fill the club at times, the Paradise kept struggling. Rockhead’s reputation would again be its saviour. In the ‘60s, Montreal’s hotels and restaurants did not have the same colour discrimination as in the US southern states, which welcomed Black tourists to come up to Canada. When they came to Montreal, they came to Rockhead’s. A few tour buses arrived at first, but soon they all flocked to the Paradise for their holidays. Year after year, the lines of buses grew as did the business. By the summer of 1973, the 300-seat club was filled in 20 minutes and the bar was out of scotch by midnight. As Rufus Rockhead simply smiled and said to Kenny, “this is just like the old days!”

The final curtain falls…

In March of 1978, Rockhead suffered a massive stroke and entered the St. Anne-de-Bellevue Veteran’s Hospital. In a wheelchair with his memory fading, Rufus Rockhead passed quietly on September 23, 1981, joining Elizabeth who had gone 19 years before him. The Paradise was sold in 1982 and finally demolished by the end of the decade. As funeral-goers paid their final respects, they could only imagine the experiences of this legendary man, a great man, a man who had once made Montreal his Paradise.

Don't it always seem to go…That you don't know what you've got til it's “gone”…

Sources

Oral history interviews with Anne Rockhead, conducted by Rohinton Ghandhi, February 14, 20 and 21, 2013, Montreal.

Robert Stewart, “Rockhead’s Paradise,” Montreal Gazette’s Show magazine, July 21, 1973.

David Sherman, “Rockhead’s is 50,” Montreal Gazette , January 2, 1979.

Brenda Zosky Proulx, “Paradise” is faded but it’s not all 50,” Montreal Gazette , May 22, 1982.

David Yates, “Friends bid goodbye to Rockhead today,” Montreal Gazette, September 26, 1981.

Ian Mayer, “Club owner Rufus Rockhead dies,” Montreal Gazette, September 24th 1981.

Dane Lanken, “Rufus Rockhead - He keeps on smiling,” Montreal Gazette, June 12, 1970.

Tom Massiah, Emanations from the Corpse of Little Burgundy, 2012.

Al Palmer, Montreal Confidential, 1950.

Marthe Sansregret, Oliver Jones: The Musician, the Man : a Biography, 2006.

Sarah-Jane Mathieu, North of the Colour Line Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870-1955, 2004.

Gerald A. Archambeau, A struggle to walk with dignity; The true story of a Jamaican-born Canadian, 2010.

Billboard Magazine January 1st 1944 and July 1st 1946 – Attraction Routes include Rockhead’s Montreal (as reference).

Joni Mitchell, Song Lyrics “Big Yellow Taxi,” From the album Ladies of the Canyon, Warner Brothers Records Inc., 1970.

To Learn More

The Maroons in Jamaica, http://www.seaworthy.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=36...

Ensemble, An Exhibition of Art and Jazz, http://www.ensemble.concordia.ca/pages.php?id=7

Burgundy Jazz -- OFFICIAL TRAILER, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzk8fGC9XmM

Oscar Peterson – C jam blues, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTJhHn-TuDY

Oscar Peterson & Count Basie - Jumpin' At The Woodside, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIs1vcoPQbw

Jitterbugs with Cab CALLOWAY in "Sensations of 1945", http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VulxJnJ0AZE

Ella Fitzgerald - Round Midnight, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEaDj6TXiQQ

I’m ready for my (you tube) close-up, Mr. Decastro site, http://yankeedollar.wordpress.com/category/rockheads-paradise/

The Padlock Law, http://www.historyofrights.com/events/padlock.html

Author

Rohinton Ghandhi is a local author/historian who loves writing stories of Montreal in times gone by, specifically stories local to Crawford Park, Verdun and LaSalle. Many of his historical stories have been published across newspapers, magazines, and on-line worldwide, including the Mosaic Montreal website. Rohinton has been digitally chronicling the Verdun Guardian for the last 5 years, from 1931 to currently 1941, as a personal preservation interest, before the pages turn to dust.