Statue of Horatio Nelson

Organization: Centre d’histoire de Montréal

Coordinates: http://ville.montreal.qc.ca

Address: 335 Place d’Youville, Montreal, Quebec, H2Y 3T1

Region: Montreal

Contact: Jean-François Leclerc, chm(a)ville.montreal.qc.ca

Description: An 8-foot tall statue of British Admiral Horatio Nelson. The original is in the Centre d’histoire de Montréal, and a replica is atop a column at the Jacques Cartier Square.

Year made: 1808-1809

Made by: Robert Mitchell, Coade & Sealy

Materials/Medium: Coade stone

Colours: cream

Provenance: London, England

Size: 2.5 m tall

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Centre d’histoire de Montréal

Nelson’s Statue

Rod MacLeod

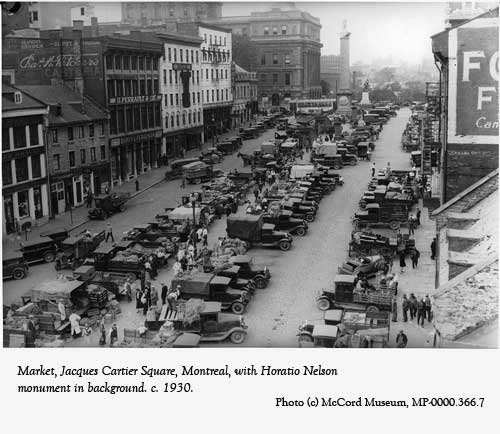

The monument to Admiral Horatio Nelson is an iconic image in Montreal, but one that most citizens do not notice – or, if they do, find either amusing or annoying. The statue stands at the top of the gently-sloping Jacques Cartier Square in the heart of Old Montreal, crowning the view upwards from St. Paul Street and forming a useful meeting point for visitors.

The observant viewer will note that the figure stands facing away from the bustle of the square, as if more interested in the mountain (which would have been visible at the time the statue was built) than in the harbour and the river beyond. For an old sailor, this is an odd preference, and may well have been an idiosyncrasy on the builder’s part. Many passersby, those who know a little history, may well resent the presence of a British war hero whose famous victory over the French seems out of place in an officially French city; this resentment has formed part of the statue’s legacy. Others, who know a little more history, realize that monuments are always complex things, and that we see them as black or white symbols at our cultural peril.

The naval battle off the coast of Spain (Cape Trafalgar) that settled a major phase of the Napoleonic Wars in Britain’s favour, but cost the victorious commander his life, took place on October 21, 1805. News of the victory took two months to reach Montreal. According to legend, a messenger arrived in the midst of a snowstorm at the home of merchant Samuel Gerrard, where a ball was in full swing, and once they had recovered from the shock, guests immediately began pledging donations for a monument.

Gerrard’s guest list was largely composed of the city’s British-born elite – Sir James Monk, Sir John Johnson, and several former fur traders, including John Ogilvy who would name his large mountain estate “Trafalgar.” But there were also plenty of leading Francophones; apparently even the Sulpician seminary had sent a representative. Enthusiasm for the monument was widespread among this group, and not merely among Anglophones as many would more recently argue. That said, patriotism came naturally to those of British stock, but for French Canadians to have cheered for Britain was an indication of considerable acculturation on their parts. Furthermore, in the current political climate at that time in Lower Canada, it was dangerous to show any sympathy for Napoleon or the ideals of the French Revolution.

It took longer than expected to raise enough money to begin construction, and for this reason Montreal lost out to Glasgow on the distinction of being the first city to honour Nelson with a monument. Monk, Johnson, Ogilvy, merchant John Richardson and notary Louis Chabouillez formed a committee to negotiate a site. They found an ideal spot, which Governor Craig donated to the cause, located at the top of the New Market, an open space recently created to replace an area destroyed by fire in 1803.

They commissioned London architect Robert Mitchell to design the statue, which was then cast by the British firm of Coade and Sealy. The statue arrived in Montreal in the spring of 1808. Construction of the ten-foot-high pedestal was supervised by local stonemason William Gilmore; the cornerstone was laid in August 1809.

Each side of the pedestal bore scenes from Horatio Nelson’s career, accompanied by inscriptions describing the various battles. The side facing the same direction as does the statue of Nelson includes the famous line: “England expects every man will do his duty.” Above the pedestal was a 50-foot cylindrical limestone pillar, on top of which the statue itself looked much smaller than its eight-foot height.

Following its completion, the column does not appear to have been held in any degree of contempt by Francophones. Indeed, no real issue arose until 1894 when a group of young Francophone men were arrested in the act of trying to blow Nelson’s column up with dynamite. It may have been in reaction to this stunt that a move six years later to restore the much-weathered monument was presented as a symbol of harmonious ethnic cooperation. The Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal, a bilingual organization dedicated to preserving local heritage, presented the monument as the product of both cultures; the Francophone head of the restoration committee even announced proudly that the monument’s original promoter had been a French Canadian, Samuel “Girard.” The news that Gerrard had in fact been an Ulsterman does not seem to have dampened the collaborative mood.

However, it would not be long before ethnic tensions rose, along with French-Canadian opposition to the Boer and Great wars. In 1927, a group of Francophones decided to erect a monument to Jean Vauquelin, a minor French naval commander during the Seven Years War. The statue was unveiled three years later on the north side of Notre Dame Street, right across from Nelson, as if daring him to sneer down at a representative of the enemy.

The association of Nelson’s column with British imperialism, and therefore English oppression, was largely a creation of the rise of Quebec nationalists in the 1960s. They were not alone in their anti-Nelson stance; the Irish Republican Army had consistently criticized the Dublin version (known as Nelson’s Pillar) and in 1966 a faction set off a bomb that damaged it so much it had to be demolished. Montreal’s monument has only been the victim of the occasional bout of graffiti and the somewhat less rare grumblings over the appropriateness of having such an obvious symbol of the British empire in a city whose majority feels no sympathy in that regard.

In 1997 when the monument’s physical deterioration was once again of concern, the suggestion was made to move it to a more Anglophone part of town. Instead, the statue found a new and suitable home in the Centre d’histoire de Montréal, a museum of local history in the western part of Old Montreal. The Nelson that stands today atop his column in Jacques Cartier Square is a replica.

Sources

Newton Bosworth, Hochelaga Depicta, 1839.

Alan Gordon, Making Public Pasts: The Contested Terrain of Montreal’s Public Memories, 1891-1930, Montreal, 2001.

Montreal Daily Star, 18 January 1894.

To Learn More

Roger Knight, The Pursuit of Victory: The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson, 2005.

Andrew Lambert, Nelson: Britania's God of War, 2005.

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.