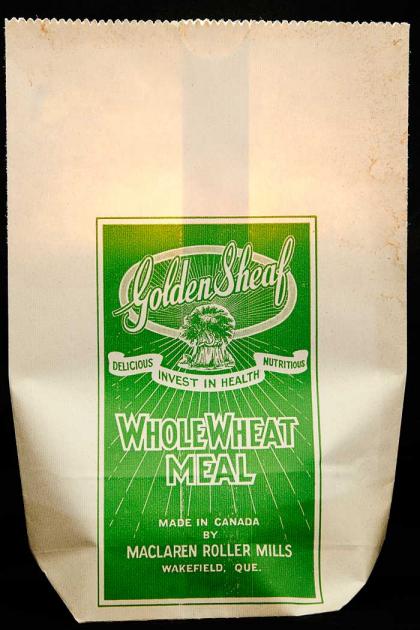

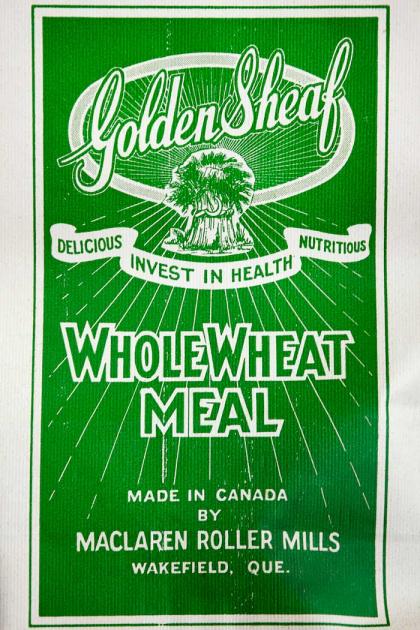

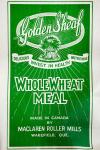

Golden Sheaf Whole Wheat Meal Package

Organization: Fairbairn House Heritage Centre

Coordinates: www.fairbairn.ca

Address: Box 195, 45 ch. Wakefield Heights, Wakefield, QC J0X 3G0

Region: Outaouais

Contact: Anita Rutledge:anitar [at] bell.net

Description: Package for MacLaren's new Golden Sheaf Whole Wheat Meal, a new cereal in the early 1900s.

Year made: circa 1920s

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Heavy weight pliable paper bag

Colours: Cream, dark green

Provenance: Unknown

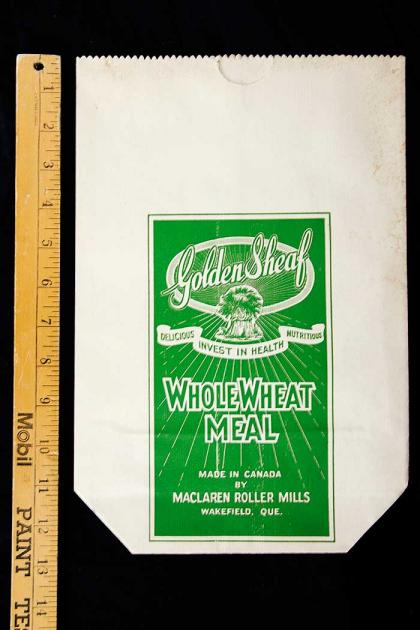

Size: 33 cm x 21.5 cm x 7 cm when filled

Photos: David Irvine. Courtesy Fairbairn House Heritage Centre

The Golden Sheaf Meal Cereal Package

Anita Rutledge

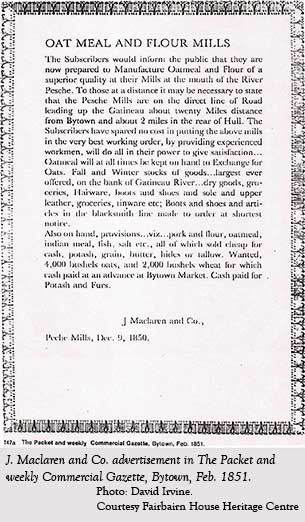

In its century of history (1838-1940), the MacLaren Flour Mill at Wakefield, in West Quebec’s Gatineau Valley, frequently adapted its operation as tastes changed and the local population grew. For instance, after it was destroyed by fire in 1910 owner Alexander MacLaren rebuilt on the original stone walls, but expanded the mill to twice its former capacity to meet growing needs.

At this same time, MacLaren introduced the latest in milling technology to produce a finer white flour, thought then to be superior to the dark-coloured coarse flour of earlier times. The expansion and up-grading made other new products possible. Wheat had become readily available after 1892 when train service reached Wakefield and brought western grain to the mill’s doorstep; this at about the same time that MacLaren progressed from grinding with stones to the roller-mill method.

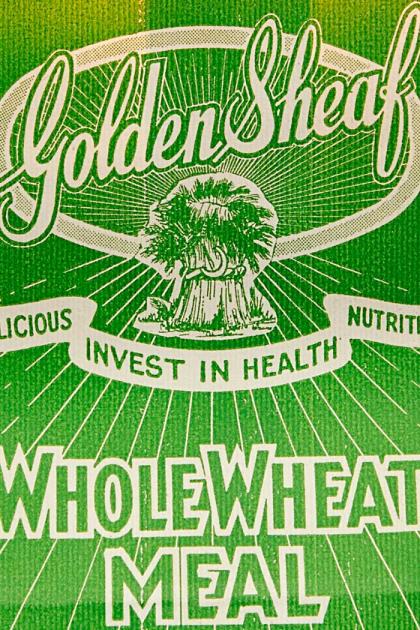

As appetites and lifestyles began to change in the early decades of the 20th century, so did Gatineau Valley families’ taste for new flours and cereals in their diet. This led to the introduction of a new cracked wheat cereal, or meal, named Golden Sheaf, to be produced at the mill with innovative and colourful packaging, and some product marketing and promotion. The new package was printed on cream-coloured heavy, but pliable paper with an attractive dark-green harvest design and lettering that read: Golden Sheaf Whole Wheat Meal • Delicious • Invest in Health • Nutritious • Made in Canada by MacLaren Roller Mills, Wakefield, Que. It was a stark departure from previous containers. The colourful new package measured approximately 33 cm x 22 cm, with a thickness of 7 cm when filled. It held about one kilogram of meal - a quantity that homemakers of the day were requesting.

As it turned out, the new package also meant some extracurricular activities for the miller of the day, with assistance from his family. The first Golden Sheaf packages required gluing and affixing labels by hand - a job that the miller’s five young daughters helped with after homework in the evenings. But first, the glue had to be mixed by the miller or his wife and heated on the kitchen stove, before it could be brushed onto the labels. In their older age, these daughters still clearly recalled the disagreeable odour of this preparation as it wafted through the rooms of their house. To add to the dismay, they had heard that the basic ingredient in the glue came from horses’ hooves!

Larger quantities of milled products continued to be sold in the traditional containers. The finest flour was sold in “98-pound” (44 kg) white cotton bags, with a ten-cent charge for the bag. At this price, a valued amount in those days, many customers brought the empty bags back for re-fill when they needed more flour. Jute bags of about the same size were used to hold coarse grains, meals, and cereals. Small wooden barrels holding slightly more product were sometimes preferred by customers.

Shorts, a mixture of bran and coarse flour, came in the jute bags, as did oatmeal, bran, ground corn, germ meal, and provender, milled from oats for animal feed. Screenings, consisting of discarded hulls, seeds and weeds after grain was milled, sold as scratch feed for poultry as well as the whole grains for seed and feed -- wheat, oats, barley and buckwheat, all were sold in jute or cotton bags, as appropriate. These bags were sealed and stitched with cotton cord, using a large hand-held curved needle. In earlier days, retail stores often wanted the coarser cereals like bran and oatmeal delivered in wooden barrels, to be scooped out and sold to customers in measured quantities.

The strong cotton and jute bags were never discarded, but filled and re-filled at the mill, or often recycled for other uses in homes and on the farms. For instance, cotton flour bags made good shirts, underwear, aprons and quilts when well washed and bleached. The new pliable heavyweight paper bag used for Golden Sheaf meal was perhaps the first non-recyclable package used at the mill; however, in a depressed time of scarce resources, its re-use by families for storage of other foodstuffs, or to pack lunches for school or outdoor work, was commonplace.

The new pre-packaged meal had other advantages. It was easily handled in grocery stores, doing away with the muss or fuss involved in measuring, weighing and re-packaging to fill orders. And, at a time when most mothers still served homemade breads, biscuits, cakes, and hot cereals to their families on a daily basis, the more adventurous new-taste and texture of the Golden Sheaf Whole Wheat Meal in its colourful package must have added a certain flair and flavour to tired old recipes.

The Fairbairn operation from 1838 to 1844 was typical of the early custom milling businesses that existed in Quebec at the time. After the mill was sold to the MacLaren brothers in 1844, it became an important part of the expanding merchant milling trade in which many English-speaking Quebecers were prominent and successful, as the MacLarens were. As the 20th century progressed, however, huge milling companies transformed the way flour was produced and packaged, and most of the earlier and smaller mills were forced to close their doors.

The old stone walls at the Wakefield mill have seen many changes in a century of growth and the paper cereal package represents one of them. Today, these same walls delight tourists in a high-end resort, a world apart from that of the settlers who worked and traded here.

Sources

Wakefield Mill sales chits, 1924-1927, Library and Archives Canada, MG30 B158 10.

Eve Lynne Ellman,“Wakefield Mill: Mill Owners, the Mill and the Community 1832 to 1980.” Report commissioned by the National Capital Commission, March 1984, revised July 1984.

Oral History Interviews conducted by Anita Rutledge with daughters of Miller Bill Bridgeman (1924-1941) 2007-2008.

Oral History Interviews conducted by Anita Rutledge with Ray Daly, aged 99, and Mae Richardson, aged 85, lifetime farm owners, 2011 and 2012.

To Learn More

Norma Geggie, Wakefield Revisited, 2003.

Ken Young,“Wakefield’s Last Miller,” Tributes: Gatineau Personalities and Historical Events by Ernie Mahoney, Oct. 2, 1986 , Gatineau Valley Historical Society, 2010.

Anita Rutledge, “Milestones in 170 Years at the Wakefield Mill,” Up the Gatineau, Volume 35 Gatineau Valley Historical Society, 2009.

Author

Anita Rutledge is a director on the board of the Fairbairn House Heritage Centre.