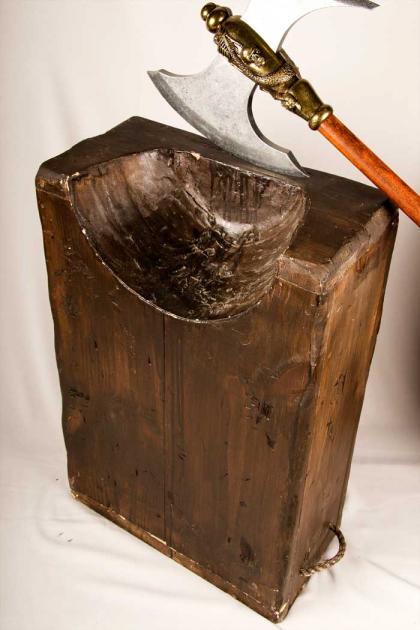

Executioner’s block (Theatrical prop)

Organization: Montreal West Operatic Society

Coordinates: www.mwos.org

Address: P.O. Box 1091, Station “B,” Montreal QC H3B 3K9

Region: Montreal

Contact: Susan Germinario, 514-990-8813

Description: a Tudor-style executioner’s block with cradle for the prisoner’s neck.

Year made: 2007

Made by: Elena Cerrolaza

Materials/Medium: pine wood, plastic, plastic wood, rope, paint

Colours: Dark brown

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 47 cm wide, 25 cm deep, 71 cm high

Photos: (1-3) Rachel Garber; (4) Rod MacLeod

Community Theatre

Rod MacLeod

There is a long tradition in English Canada of “amateur dramatics” – people without formal training putting on plays in local auditoriums or church halls. Such people often possess considerable raw talent, and there is no way of knowing how many in the past might have become professional performers, given the lack of theatre schools in Canada until well into the 20th century.

Originally, however, theatre was less about talent than it was about community. Everything was home-grown. Ministers and lady teachers often spearheaded dramatic productions, drawing the cast from a cross-section of the local population; taking part was an aspect of civic life, and it kept kids off the streets and men out of bars. Many small towns had their divas, typically well-to-do women whose husbands were local businessmen. Ladies’ guilds could sew costumes; Sunday painters could produce scenery. In recent years, the phrase “community theatre” has emerged as a more accurate term to describe the collaborative efforts that go into most productions.

Professional theatre in English-speaking Quebec has its roots in community theatre. By the 1930s, Montreal sported several companies: the Community Players, Trinity Players, St Lambert Players, the Weredale Dramatic Group, the Little Theatre at the YMHA, the McGill Players, and most famously the Montreal Repertory Theatre. None of these were professional companies per se, although most featured performers who would go on to be well-known actors and for whom a stint in community theatre meant much-needed exposure.

These groups would have tackled musical shows from time to time if there were singers in their midst, although the complicated choreographies of Broadway were beyond many performers and impossible in most venues. His Majesty’s Theatre on Guy Street attracted New York road shows and occasionally opera troupes. The Canadian Opera Company, established in Montreal in 1931, featured some local talent alongside imported stars, but for the most part actors with an interest in singing had limited opportunities.

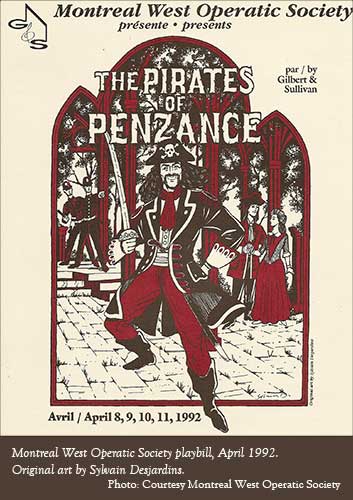

England’s answer to musical theatre, Gilbert and Sullivan, was ideally suited to community groups with few resources but considerable skills, given its emphasis on sound over choreography. “G&S” did not catch on in Canada until the fabled London D’Oyly Carte Company toured the colonies in the winter and spring of 1927. This was the first time the company had gone on tour internationally, and it was musical director Harry Norris’s job to see that audiences were entertained by the elaborate melodies, playful lyrics, and ridiculous plots.

They were – but what was more significant, Norris was quite taken with Montreal; two years later he and his wife Doris decided to move there permanently. Norris taught music at McGill, but also directed choirs around the city. His favourite group was at the Montreal West United Church near where the Norrises lived. In the summer of 1939 he suggested to the townspeople that they stage The Pirates of Penzance, the D’Oyly Carte Company’s first big success. Doris, also a former member of D’Oyly Carte, took on the role of stage director, leaving the musical direction to her husband. The cast was largely drawn from the city’s West End; the audience came from even further afield to the undistinguished auditorium in Montreal West High School. Critics raved. The Montreal West Operatic Society (MWOS) was born.

In classic community theatre tradition, all members of the society took part in the annual productions, if not as performers then as stage or costume crew or other aspects of company management. During the postwar period, the non-performing wives of MWOS members sewed and organized and raised funds just as they did in church and their children’s schools. Non-performing husbands sat on the MWOS board of directors and used their business contacts to attract sponsors and promote the shows as good family entertainment.

Success meant more lavish productions, mounted in the state-of-the-art theatre in Notre-Dame-de-Grace’s West Hill High School. The company regularly hired professional set, costume and lighting designers, although it was a rule that no performer would be paid. Harry and Doris Norris also adapted the MWOS model to other communities eager to try G&S, notably Town of Mount Royal, St. Lambert, and Lachine – the latter becoming the Lakeshore Light Opera, which like MWOS and the McGill Savoy Society (founded 1964) survives today. The Norrises remained active until the late 1960s when they pulled up roots again and retired to England.

Success in theatre depends on enthusiastic audiences, of course. By the 1960s, operetta was a tougher sell to young people than it had been, although seasoned patrons remained loyal. By the 1970s, as with everything else in Quebec, this cohort of patrons began to thin, through both natural attrition and out-migration. By the 1990s, MWOS continued to flourish, but drew members and audiences from further and further away as the pool of local talent diminished. In the early 2000s, the crunch came: the company was deep in the red and could not continue with the kind of lavish productions it had grown used to – if it could continue at all.

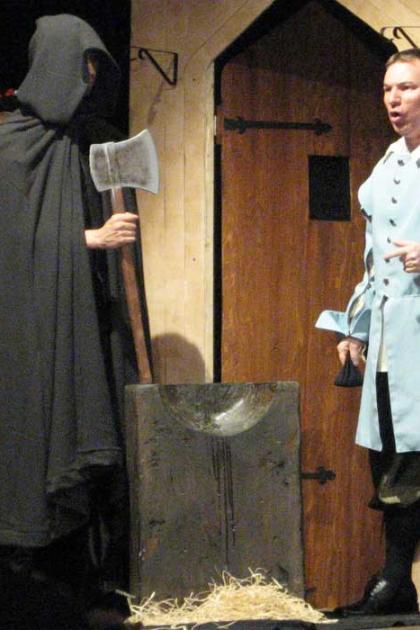

The solution was a return to a purer form of community theatre, where members no longer rely on professional support but tap into their own skills, be they artistic or managerial. From within the group emerged art teachers, carpenters, fashion designers and public relations specialists who had originally signed on merely to perform, but who welcomed a chance to put the skills they were never paid for to good use. Consequently, MWOS has assembled a collection of adaptable costumes, set pieces, and bizarre props ranging from a birdcage hairpiece for The Gondoliers to a blood-stained chopping block for Yeomen of the Guard. Improvised by locals with local materials, such relics speak directly to the “community” in community theatre.

Over the years, as members come from further away, MWOS has diversified. The entirely white, middle-class and unilingual nature of 1940s and 50s Montreal West and its resident operatic society is long gone, in keeping with the growing cultural variety evident within the English-speaking population in general. There is even a significant number of Francophones who have braved the notoriously difficult rhythmic and diction requirements of WS Gilbert’s fantastic patter songs.

The audiences they connect with and draw to MWOS performances are no longer unfamiliar with – in many cases are quite obsessed by – English-style musical theatre. As ever, there is nothing amateurish about the society, which provides useful opportunities for aspiring actors to gain valuable experience, particularly the chance to sing in four-part harmony; similarly, it enables even established singers an occasion to act.

Sources

Montreal West Operatic Society Archives

Janet Allingham, “Music, Relationships and Community: A Childhood with the Montreal West Operatic Society,” Quebec Heritage News, March 2010.

To Learn More

Montreal West Operatic Society http://mwos.org

Opera in Canada http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/emc/opera-performance

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.