Chisasibi Cree Hunter’s Snowshoes

Organization: Cree Nation of Chisasibi and the Chisasibi Cultural Centre

Address: Box 584, Chisasibi, QC J0M 1E0

Region: Northern Quebec

Contact: Felicity Fanjoy, felifan [at] hotmail.com

Description: Wood and rawhide snowshoes handcrafted by Cree people of Chisasibi for use in walking over the snow. Although the techniques of fabrication have remained unchanged for centuries, the design has gradually evolved and been adapted to regional winter conditions in Eeyou Istchee, the Cree territories of James Bay, Quebec.

Year made: 2012

Made by: Reggie Fireman and Louise Rednose Fireman

Materials/Medium: Wood, animal hide, wool

Colours: Natural, multicoloured wool

Provenance: Chisasibi, Quebec

Size: 132 cm x 33 cm

Photos: (1-3) Rachel Garber, (4) Felicity Fanjoy

Chisasibi Cree Hunter’s Snowshoes

Felicity Fanjoy

In northern Quebec, Cree territory encompasses approximately 400,000 square kilometers of land lying mostly north of 50° latitude. The Cree Nation of James Bay is comprised of five coastal communities – Waskaganish, Eastmain, Wemindji, Chisasibi and Whapmagoostui – and four inland communities – Nemaska, Waswanipi, Oujé-Bougamou and Mistissini. The Grand Council of the Cree claims that they have held their traditional ancestral lands east of Hudson and James Bays since “time immemorial” and archaeological studies have confirmed the presence of the Cree beginning approximately 6,000 BC. The name Cree is derived from the Algonquin linguistic family and means “the people.” Their own name for themselves is Eeyou which also means “the people.”

The Cree Nation of Chisasibi is a village of about 4,000 people, situated on the banks of La Grande River near the shores of James Bay. It is the largest of the nine Cree communities. About 300 Inuit are permanent residents, and perhaps the same number of mostly-transient non-Native people reside there for employment. The great majority of the population speak Cree as their mother tongue, with English as the dominant second language of the community.

Whether the indigenous peoples of Quebec adopted French or English as their second language depended almost entirely upon geography. Waterways provided the paths inland for early European explorers. The French travelled up the St. Lawrence and along its tributaries and connecting chains of lakes while the British sailed the eastern seacoast northward, then down into Hudson Bay and James Bay to the rivers that flow into those great basins. The explorers were followed by fur traders and then Roman Catholic and Protestant missionaries who brought with them Christianity and education in their own mother tongues. Consequently, the more southern First Nations such as the Huron and Abenaki now speak French, while the northern First Nations of Cree and Inuit, who have more successfully retained their own mother tongues, overwhelmingly speak English as their second language.

The Cree were a nomadic people whose survival depended upon their ability to track and hunt migrating game. In a land where winter lay deep upon the taiga and boreal forest for half the year or more, being able to move lightly across the surface of the snow rather than trudge through waist-high drifts was imperative. Thus, the snowshoe, which has been in continuous use in this region for thousands of years, was conceived and perfected.

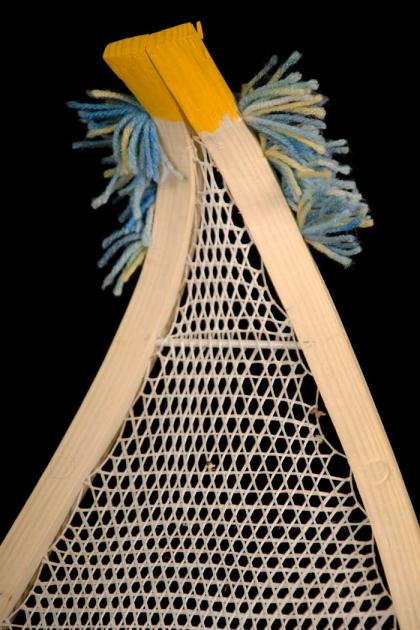

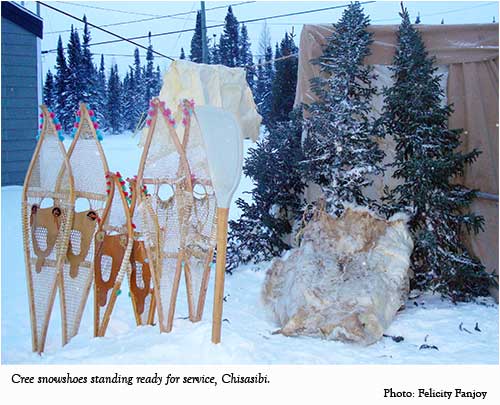

The distinctive canoe-shaped snowshoe that is commonly used today among the Cree of Chisasibi is ideally adapted to its environment: the long, narrow profile allows it to pass through the bush more easily than the rounded snowshoes found in other regions, and its large surface area and fine mesh keep it afloat in even the deepest powder snow. The upturned prow prevents it from digging into impeding snow drifts and slowing down the hunter. This elegant piece of ancient technology enabled a people to thrive in an environment that most would consider uninhabitable.

Made of carefully selected tamarack or birch wood and strips of moose or caribou rawhide, a large pair of hunter’s snowshoes can be assembled in about a week to ten days, once the materials have been obtained. Traditionally, this work is done by a man and woman. The man searches for a suitable tree and cuts the wood, and he hunts the caribou or moose. Then it is the woman’s job to scrape and prepare the hide which is cut into narrow strips of varying thickness. The man shapes the snowshoe frame using a handmade carving tool with a curved blade, and by dipping the wood in boiling water in order to make it flexible.

Once the desired form has been achieved, the paired sides are bound together around struts that hold the curves in place, and the frames are suspended over an open fire for about four days. This dries and hardens the wood into its permanent form. Next, the man drills holes in the frame for the birch cross bars and the webbing. Once the crossbars have been inserted, he attaches anchor cords for the webbing along the inner edges of the frames. Then the woman can begin weaving the fine mesh at the front and back ends of each snowshoe. The heavy centre webbing is done by the man because it is tough and must really be pulled tight in order to be sufficiently strong, as this is the part of the snowshoe that supports the foot.

Finally, the decorative elements are added. The front and back tips may be brightly painted and tufts of dyed wool added along the sides. These are not mere frivolous adornment. It is believed that colours speak to the spirit of animals. Traditionally, a hunter’s clothing and equipment were always beautifully decorated in order to please the game and to create a spiritual bond between hunter and prey, making the animals more willing to sacrifice themselves to the hunter.

The finished snowshoes must always be treated with great respect because they are the most valuable piece of equipment that a hunter owns. Therefore, they are never simply thrown on the ground when taken off but always placed together upright in the snow facing east to greet the rising sun or hung in trees at camp to protect them from animals that might chew on the webbing.

Traditional legends and modern stories are told about how snowshoes have saved people’s lives. One ancient tale tells of talking snowshoes that roused a sleeping hunter to warn him of coming danger, then carried him to safety. Even today, a snowmobile can break down in the wilderness, but a good pair of snowshoes will always carry you back home.

Sources

Oral history interview with Margaret and Samuel Bearskin, Cree elders and teachers of traditional snowshoe making. “Waaskimaashtaau Newsletter,” February 2013: Brighter Futures Department of the Cree Nation of Chisasibi.

Examples of Cree snowshoes can be seen on display at the Administrative Centre of the Cree Nation of Chisasibi in Chisasibi, Quebec, and at the Aanischaaukamikw Cree Cultural Institute in Oujé-Bougamou, Quebec.

Images of Cree snowshoes can also be seen at www.creeculturalinstitute.ca in various video segments and on page 3 of the Virtual Exhibit where they are labelled “swallow-tailed snowshoes” and referred to as “Chisasibi-style snowshoes” in the extended description.

To Learn More

Toby Morantz, “An Ethnohistorical Study of Eastern James Bay Cree Social Organization 1700-1850,” Canadian Ethnological Service Paper #88, 1983.

Brad Martin, Home is the Hunter: The James Bay Cree and Their Land, 2010.

The Cree Living Language Encyclopedia Project, “Snowshoe, Sunrise and Fish Song,” Joseph Rupert at www.eastcree.org

Author

Felicity Fanjoy is a teacher and writer who has resided in Chisasibi, Quebec, for almost 30 years.