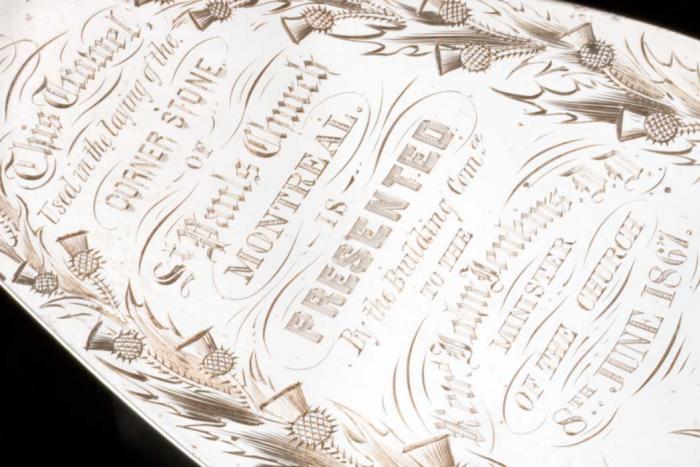

Silver Trowel

Organization: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Coordinates: http://www.mbam.qc.ca

Address: 1380 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, QC H3G 1J5

Region: Montreal

Contact: Danièle Archambault, darchambaul(a)mbamtl.org

Description: Silver plasterer’s trowel used in the laying of the cornerstone for the new St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church in Montreal.

Year made: 1867

Made by: Savage & Lyman

Materials/Medium: Silver

Colours: Silver

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 20 cm long

Photo: Courtesy Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal

Building Presbyterianism

Rod MacLeod

The cornerstone of Montreal’s new St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church was laid on June 8, 1867, on the south side of Dorchester Street (now René-Lévesque) west of University Avenue. A layer of cement was symbolically applied with a silver trowel by the Reverend John Jenkins, St. Paul’s new minister.

The trowel was specially commissioned for the occasion by the church’s building committee, three Scottish businessmen who would have a profound influence on the city’s, and the nation’s, development: George Stephens (textile merchant and future president of both the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Bank of Montreal), Andrew Allan (of the Allan Line shipping company), and Donald Ross (dry goods merchant and founder of the institute that would become Trafalgar School for Girls). Presbyterianism was a powerful force in 19th-century Canada, and nowhere was it more powerful or influential than at St. Paul’s.

There had been Presbyterians in Quebec as long as there had been Scots. The preponderance of Scots within the colony’s economy since the British conquest may have had something to do with the Calvinist work ethic that often characterizes Presbyterianism. More likely, however, it derived from the grim determination to succeed felt by many Scots who came to see their cultural domination by the English as an opportunity rather than a curse. As social underdogs often do, Scots strove to make their mark, and did so through family, business and church networks. They were particular about church: from the early days of British rule, Scots resisted government pressure to make Anglicanism (the Church of England) the only established non-Catholic religion in the colony; their resistance paved the way for the recognition of the rights of other religious groups, albeit not until the 1830s. In 1791, Scots built Montreal’s first permanent place of non-Catholic worship: the St. Gabriel Street Presbyterian Church. As the Scottish community grew, so did internal disputes. By 1803 a separate congregation, St. Andrew’s, was founded, followed in 1822 by another, the American Presbyterian Church, serving Presbyterians of American origin. In 1831, a more serious rift (“a scene of great religious scandal with much pain”) between the Gabriel Street minister, Henry Esson, and his assistant, Edward Black, resulted in the founding of yet another splinter congregation, this one consisting of some of the city’s wealthiest families.

St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church was built in 1834 in Montreal’s old town at a cost of over £3,500. It was (according to the Montreal Gazette) a “chaste and elegant building” combining traditional Neo-Classical elements with more forward-looking Neo-Gothic features. In keeping with the Presbyterian emphasis on education, the congregation also paid for a permanent home for the school Reverend Black had been teaching. Located next to the church, Black’s Academy taught the sons of the city’s leading families – Redpaths, Greenshields, Baggs, Frothinghams, and Molsons – not all of them Presbyterians. Black taught with the help of two assistants and his daughter Eliza, who was apparently “the idol of the boys.” (One of them later married her.)

Presbyterians were particularly active in public education. Before the middle of the century, Anglicans enjoyed a disproportionate influence over government funding for schools, and other non-Catholics often resorted to sending their children to private academies such as Black’s. When common schools were created in 1841, Anglicans developed their own system, seeing the new legislation as an attempt to impose a Scottish-style community-based form of education on the new Province of Canada.

With few resources, Montreal’s Protestant school system was slow to take shape, but did so in time largely thanks to the leaders of St. Paul’s church. Black’s successor, the Reverend Robert McGill, became chair of the Protestant Board of School Commissioners (PBSC) in 1848, and over the following three decades, ministers of St. Paul’s also served as chairs of the school board. Mindful of their history of resistance to religious hierarchy, these ministers presided over an essentially non-denominational form of education.

With the approach of Confederation, Protestants of all stripes grew fearful of being overwhelmed in the new province of Quebec by a majority Catholic population. Even Anglicans were now willing to join with Presbyterians in a campaign to have minority education rights enshrined in the British North America Act. This campaign was led by the new chair of the PBSC, the Reverend John Jenkins. The Welsh-born (and formerly Methodist) Jenkins appears to have had a knack for uniting differing denominations. He brought onto the school board Methodists such as James Ferrier, who as a senator helped ease the passage through the legislature of school tax reform that substantially increased government spending on education. Protestants benefited especially from this reform, and were able for the first time to launch a program of school building.

Another new school commissioner was the arch-Presbyterian John William Dawson, principal of McGill University, who arranged for the transfer of the famous High School of Montreal from McGill’s jurisdiction to that of the school board; from this point on, the PBSC could boast a network of elementary schools across the city feeding into the High School, which was eventually made co-educational. For the rest of the 19th century and for much of the 20th, Presbyterian ministers continued to take the lead in public education, reflecting the importance of schooling to the Presbyterian tradition.

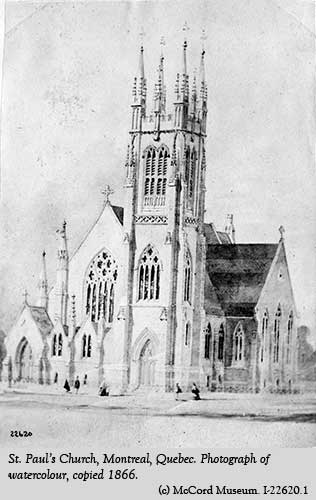

Jenkins also presided over the move uptown. The St. Paul’s congregation was growing and its old church clearly inadequate. In the 1860s, with the closing of the St. Antoine cemetery and its redevelopment as a park (Dominion Square), Dorchester Street offered plenty of building opportunities. The congregation’s building committee sold the old church, and with the proceeds purchased land on the higher ground. British architect Frederick Lawford provided the designs for a grand new Gothic structure to rival in scale and décor anything in the city – at least until the completion of the new Catholic cathedral nearby. Local architect John William Hopkins supervised the construction; the church held its first service in September 1868.

It would stand proudly on that spot until 1930, when the land was acquired by the Canadian National Railway for its new terminus. Curiously, the church itself was purchased by les Pères de Sainte-Croix and faithfully rebuilt next to their college (now a CEGEP) in Ville Saint-Laurent, where it serves as an encouraging symbol of heritage preservation – though with only scant reference to its origins as the benchmark of Quebec Presbyterianism.

Sources

J.S.S. Armour, Saints, Sinners and Scots: A History of the Church of St. Andrew and St. Paul, Montreal, 1803-2003, Montreal, 2003.

Newton Bosworth, Hochelaga Depicta, Montreal, 1839.

Report of the Protestant Board of School Commissioners for the City of Montreal, 1871.

English Montreal School Board, Minutes of the Protestant Board of School Commissioners.

To Learn More

Church of St. Andrew and St. Paul, Montreal, www.standrewstpaul.com

Musée des Maitres et Artisans du Québec, Ville St-Laurent, http://www.mmaq.qc.ca

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.