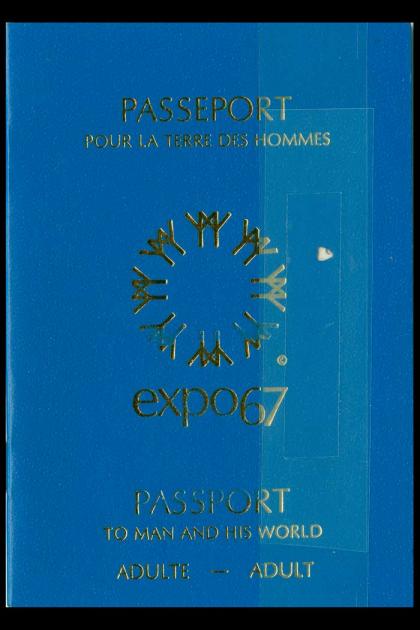

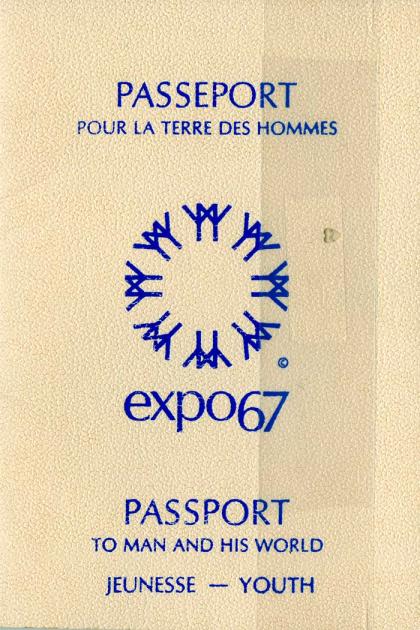

Expo 67 Passport

Organization: McCord Museum

Coordinates: www.mccord-museum.qc.ca

Address: 690 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, QC, H3A 1E9

Region: Montreal

Contact: Nora Hague, info(a)mccord.mcgill.ca

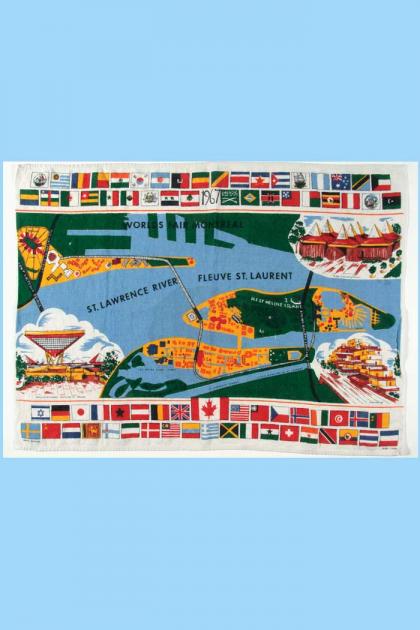

Description: (1-2) Small blue booklet full of stamps representing visits to the world pavilions at Expo '67 in Montreal; (3) Souvenir Tea Towel from Expo 67; (4) Expo 67 Wheel used to locate pavilions.

Year made: 1967

Made by: Expo 67

Materials/Medium: Paper

Colours: Blue

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 12 cm high x 9 cm wide

Photos: Courtesy McCord Museum

1967 Passport to the World

Rod MacLeod

In 1967, barely three years after Canada’s new red maple-leaf flag had deeply divided both parliament and public, and in the midst of seemingly mounting terrorist attacks by groups seeking to establish an independent Quebec state, thousands of people in the Montreal area adopted a strikingly flexible form of identity: they acquired passports that would make them, at least for a while, citizens of the world.

Despite the bitter and even violent arguments going on in the background, Expo 67 succeeded in presenting a bilingual and bicultural vision of its host country, which astonished visitors. In Quebec, Expo meant the awakening of a society that had looked inward for too long. This was no less true for Anglophones than for Francophones: indeed, for many the Expo passport was a way to shuck generations of unilingual Anglo-Saxony and embrace cultural diversity. In Montreal, where the world came to visit for six months, locals found countless opportunities to explore, to experiment, to share, and to show off.

The world came to Montreal in specific forms: the long-haired and mini-skirted British pop scene, French fine art, the kangaroos of Australia, the agricultural traditions of a China in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, the mathematics and medicine of India, and the infinite variety of Czech genius displayed, to those who could manage the long wait to get in, as Baroque altarpieces, mechanical dolls, and metafictional movies basking in the thaw of the Prague Spring. Montrealers mixed with these cultures and savoured the achievements and ambiguities of more complicated histories than their own. These cultures, moreover, were presented in pavilions of extraordinary architectural diversity: some ultra-modern, such as France and the United States, but others surprisingly traditional, like China and Burma.

One of the popular souvenirs from Expo was a cardboard wheel with a series of windows which, when aligned, showed the name of each country represented at Expo, its flag, and a picture of its pavilion. (This was by way of contrast to the tackier souvenirs on sale, such as the vibrant tea towels showing Expo as though it were a Canadian form of Royal Wedding.)

With international culture came international food and drink. Most pavilions had restaurants, so Montrealers could taste dishes they had only heard about – or never heard of: black bean Habanera, smoked reindeer, Russian caviar, Flemish smoutevol, tandoori chicken, falafel (which a journalist described as “Arabic beans ground into a savory dip served with pita bread, a crusty pocket of baked dough”), and Ethiopian coffee (whose “mahogany-brown color was as beautiful as the native waitress in a gold-filigreed cotton wrap who poured it for me”).

Montreal had a long way to go as a gastronomic capital, but it got its start at Expo. Locals lapped it up and made mental notes for later; for Anglophones, the tastes of Expo were like nothing they were used to at home or in eateries in the West End, let alone the West Island. Many Montrealers were also getting hands-on experience in restauranteurship, be it in the kitchen, serving clients, or designing and building dining facilities.

Indeed, for creative people in many fields, Expo provided golden opportunities. The most influential Anglophone involved in the fair was Robert Fletcher Shaw, a McGill-trained engineer who became the deputy commissioner-general of the Universal and International Exhibition, and in practice the general manager of Expo. Dutch-born Sandy van Ginkel, who had led the battle to save Old Montreal from demolition in the early 1960s, was put in charge of developing the Expo Master Plan. He brought his graduate student on board, Moshe Safdie, who turned his McGill Master’s thesis into one of the iconic Expo buildings: Habitat 67, a vision of future housing that became a much sought-after residence. Other McGill architects and planners – John Bland, Hazen Sise, John Schreiber – were responsible for the design of “theme” pavilions such as “Labyrinth,” “Man the Producer,” and “Man the Explorer,” and for “Children’s World” at La Ronde, Expo’s funfair section.

According to Jane Needles, today a renowned expert in arts management, Expo marked a turning point for Quebec artists, both Anglophone and Francophone, and put Montreal on the cultural map. Needles left her theatrical upbringing in Stratford, Ontario, and moved to Montreal just so she could be a part of Expo. She was hired as one of 24 stage managers running the extravaganzas at the Autostade, the stadium built for Expo. On the programme were the Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo, the Gendarmerie Française, the Great Western Rodeo, and the “Flying Colours” spectacle produced by Radio City Music Hall’s Leon Leonidoff, in which Maurice Chevalier arrived in a pale blue top-down Cadillac surrounded by exotic birds; Needles also got to ride an elephant for the three-hour journey from the train depot to the Autostade, the usual elephant girls having refused to brave the cold Montreal dawn.

Expo gave work like this to local technical talent, but this was just the tip of the cultural iceberg. Countless international stars and troupes gave local hopefuls the chance not just to see them, but to network and even to impress. And the world was impressed; it learned for the first time that Canada had a huge talent pool in all aspects of the arts. Certainly Expo gave a boost to local Anglophone theatre: audiences saw not only the opening of the Saidye Bronfman Centre in September 1967 and the Centaur Theatre two years later, but a host of smaller companies that would win acclaim and showcase native talent. In theatre as in other areas, Expo was both a stage on which the world played and a window onto wider opportunity.

The educational promise of Expo 67 was not lost on Quebec schools. As the fair was open from late April and did not close until the end of October, there were plenty of chances for class trips – which were, for many children living at a distance from Montreal, the only way they would get to Expo; not all families could afford to travel into the city, and, unless they had friends in town, staying overnight was an expensive prospect. To compensate, English schools across southern Quebec organized visits. In some communities, putting children on a bus for a two-hour journey to the city was a worrying prospect for parents, who nevertheless recognized the advantages such a trip would bring. For the children of Coaticook, a visit to Expo might have seemed all but impossible given the distances; nevertheless, a fundraising campaign was undertaken by the local Home and School Association and the Oddfellows Lodge to offset the $1.50 per child cost of the trip.

For anyone in the Montreal area, however, the best deal in town was the Expo passport, which for $35 offered an adult unlimited access to the fair for the entire season. For many, these passports ended up stamped by dozens of world nations – more than anyone could expect to actually visit in a lifetime. It was an illusion, but it left a solid sense of sophistication.

Sources

Robert Fulford, This Was Expo, Toronto, 1968.

Sandra Martin, “Sandy van Ginkel rescued Old Montreal from freeway developers,” Globe and Mail, August 23, 2012.

Interview with Jane Needles.

Frank Rasky and others, “The Wondrous Fair,” The Canadian Magazine, Vol. 3, No.24, June 17, 1967.

To Learn More

Expo 67 in Montreal: http://expo67.ncf.ca

Library and Archives Canada virtual exhibition: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/expo

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.