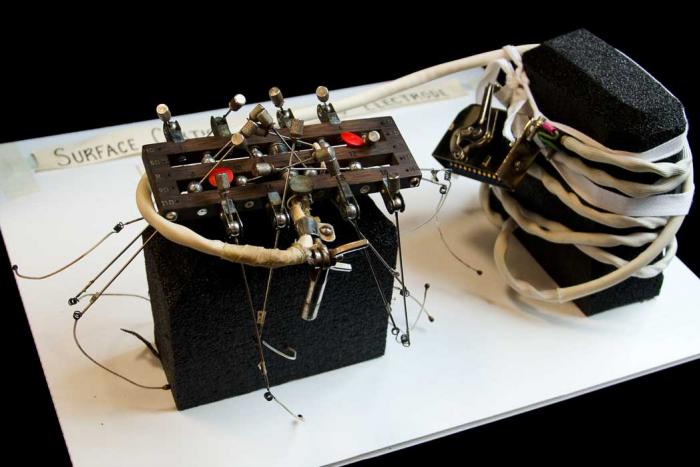

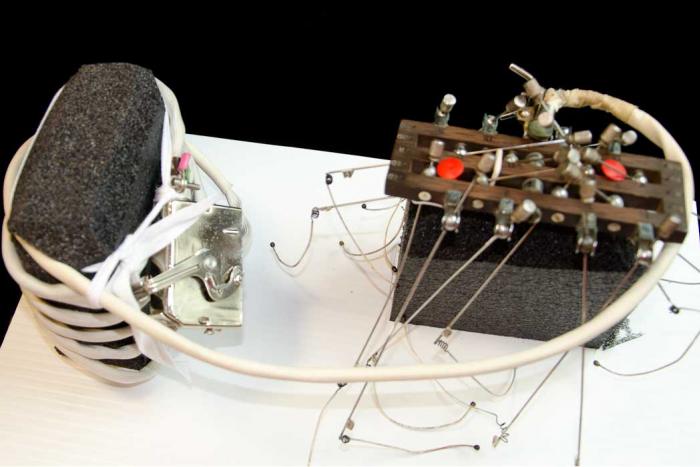

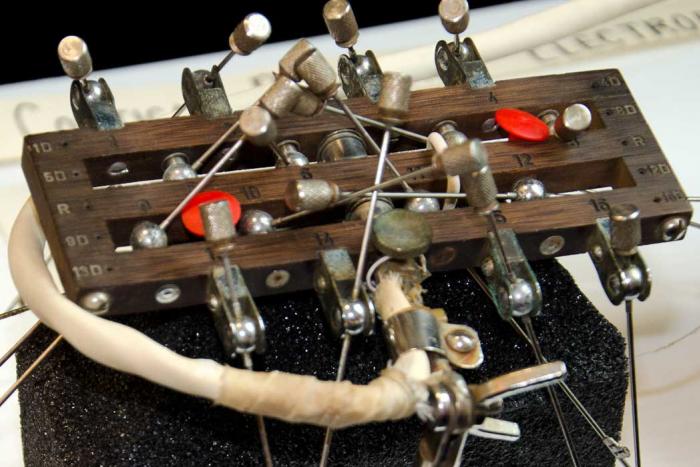

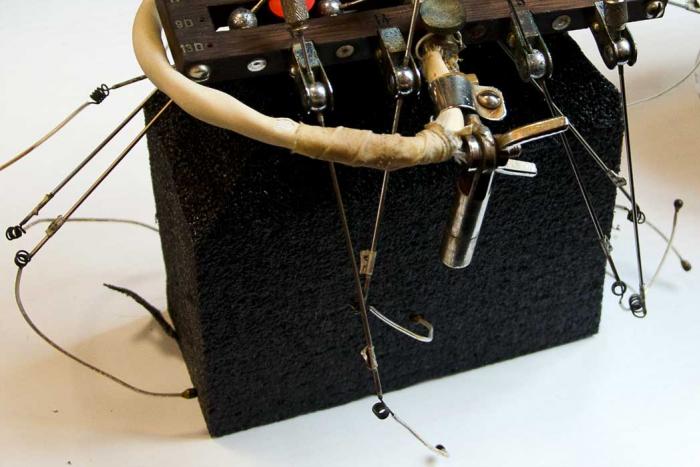

Dr. Wilder Penfield’s Recording Electrodes

Organization: Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University

Coordinates: www.mcgill.ca/library/library-using/branches/osler-library

Address: 3655 Promenade Sir William Osler, Montreal, QC H3G 1Y6

Region: Montreal

Contact: Christopher Lyon, christopher.lyons(a)mcgill.ca

Description: Surface Cortical Recording Electrodes invented by Dr. Wilder Penfield. It is an electrocorticography device used to record activity in an exposed brain during an operative procedure.

Year made: circa 1940

Made by: Unknown

Materials/Medium: Metal

Colours: Silver, black

Provenance: Quebec

Size: 15 x 13 cm (electrodes), 7 x 6 cm (recorder), 1 metre long (cable)

Photos: Rachel Garber. Courtesy Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University

The Man Behind Immersion

Rod MacLeod

Quebec has been home to an impressive list of scientists whose discoveries have transformed the modern world, including William Osler (medical training), Earnest Rutherford (radioactivity), Carrie Derick (genetics), and Donald Hebb (psychology). Not all these figures were originally from Quebec, and in many cases their most significant contributions were made elsewhere, but Canadians are proud of their own, however that is defined. A case in point is Wilder Penfield, who grew up in the United States, studied at Princeton, Oxford, and Johns Hopkins, and had a career in New York before going to Montreal in 1928 at the age of 37.

Despite this late start as a Canadian icon, Penfield earned his cultural stripes through a lasting legacy for his adopted country – above all his revolutionary discoveries in the field of neurosurgery and his founding of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI). But for Quebec Anglophones, Penfield’s particular legacy has been to provide the scholarly underpinnings for one of English-speaking Quebec’s greatest exports: French Immersion.

At the MNI (or “the Neuro” in common Montreal parlance), Penfield set out to understand how the human brain worked, with an eye to curing diseases such as epilepsy. He decided to experiment on living brains: a patient would be given a local anaesthetic and so remain conscious while Penfield removed the top of the skull and probed the brain. As patients described their reactions to different stimuli, Penfield could locate the source of an epileptic’s seizure. This revolutionary “Montreal procedure” (famously dramatized in one of the Historica-Dominion “Heritage Minutes” videos) would cure over half the epilepsy cases that came to the MNI.

Penfield designed and manufactured a series of very fine scalpels for use in minute brain exploration. He also created a spider-like device that would enable brain activity to be recorded: silver wires attached to different parts of the brain were connected to electrodes mounted on flexible joints to produce an accurate recording known as an electrocorticogram. Modern medicine’s use of electrocorticography can trace its history back to Penfield. Further studies of brain function led to a greater understanding of how memory and language worked. One of Penfield’s conclusions was that the ability to acquire language is at its peak in the early stages of human development: ages three to seven.

Such findings were of great interest to Anglophone parents in various parts of the province who were growing concerned by the 1960s that their children did not have a good enough command of French to function in contemporary Quebec. In English-language schools, French had always been taught essentially as a foreign language: something that was good to learn as part of formal education, but of no practical use. The preliminary reports (early 1965) of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (set up by Prime Minister Lester Pearson to assess the state of language and culture in Canada) presented a vision of a nation in which French was as important as English and both languages should have official status.

Clearly the way French was taught would not help English speakers communicate with their French counterparts, let alone work in French milieus. Penfield’s research suggested that Anglophone children should be exposed to French at a younger age, in the early grades when their brains were most adaptive. Protestant school boards had begun doing this in the mid-1950s; with the help of the Quebec Federation of Home and School Associations, they also developed the innovative “French Without Tears” program, which emphasized everyday communication.

Making learning French fun was the inspiration behind the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s beloved children’s show Chez Hélène, first produced in 1959 but moved to a weekday morning timeslot, for pre-schoolers, in 1963. The program featured Hélène (Baillargeon), who spoke only French, Louise (Madeleine Kronby), who was enviably bilingual, and Suzie the Mouse (a puppet), who communicated only in English; a generation of Anglophones appreciated the matronly Hélène’s wise patience and clear diction, while they identified with Suzie’s innocence and curiosity.

Exposure to French at an early age was a good idea, but surely the best way to acquire another language was to be exposed to more of it. In 1965, two unrelated groups of Anglophone parents – at Roslyn School in Westmount and Margaret Pendlebury School in St. Lambert – each presented a plan to their local school boards for introducing what they called a “Language Bath,” wherein children would spend almost the entire school day in French. Westmount had reservations, but St. Lambert was keen to try the experiment, encouraged by the work of Penfield and more directly by his younger colleague, Walter Lambert, whose studies of the psychology of language learning suggested the efficacy of what came to be called Immersion.

In the fall of 1966, Margaret Pendlebury School began to offer French instruction in all subjects to its earliest grades, with some English introduced gradually to the higher grades. This arrangement became known as the “St. Lambert Model,” and was eventually adopted across Quebec and the rest of Canada. Over time, variations emerged on the amount of English to introduce and at what stage; by the 1990s, most Protestant boards were offering quantities of French instruction ranging from about a third of the school day to 90%.

All this required more teachers capable of working in French – and led to a decline in the number of unilingual Anglophone teachers. Legally prevented from employing Catholic teachers, Protestant boards had traditionally hired Anglophones with some competency in French – many of them were from Scotland, curiously – or else teachers from French-speaking parts of North Africa and the Middle East. A 1969 law removed these limitations, and English Protestant schoolchildren began to encounter Francophone teachers from Quebec, some even with traces of Joual. This, too, was a revolution – as well as a revelation.

French Immersion owes its inspiration to parent groups working within the Protestant school system, but it took firm root in Catholic schools as well. In 1968, the Catholic school board in Dollard-des-Ormaux on the Island of Montreal decided to name its new school Wilder Penfield Elementary.

Penfield attended the opening ceremonies and during a tour took great interest in the school’s layout and design. The principal, not entirely sure about how well his own children would do learning in a French environment, asked the elderly neurosurgeon his views on language acquisition.

“A child’s brain is like a sponge,” Penfield replied, “capable of absorbing much and varied information. Barring the presence of specific learning disabilities, we could have them learn three or four foreign languages and they would not be confused – assuming, of course, that the instruction was well done.”

It is to such convictions that several generations, now, of Anglophones owe their mastery of French and their acceptance into the Quebec workforce.

Sources

Peter R. Johnson, commentary on “A Bedside Conversation with Wilder Penfield,” http://www.cmaj.ca/content/183/7/745/reply

Jefferson Lewis, Something Hidden: A Biography of Wilder Penfield, Halifax, 1983.

Library and Archives Canada, “Dr Wilder Penfield,” http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/physicians/030002-2400-e.html

PSBM Annual Reports.

Archives of the Quebec Federation of Home and School Associations.

To Learn More

Heritage Minute: https://www.historica-dominion.ca/content/heritage-minutes/wilder-penfield

Author

Rod MacLeod is a Quebec social historian specializing in the history of Montreal’s Anglo-Protestant community and its institutions. He is co-author of A Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801-1998 (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2004); “The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalisation, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2003); “Little Fists for Social Justice: Anti-Semitism, Community, and Montreal’s Aberdeen School” (Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2012). He is the current editor of the Quebec Heritage News.